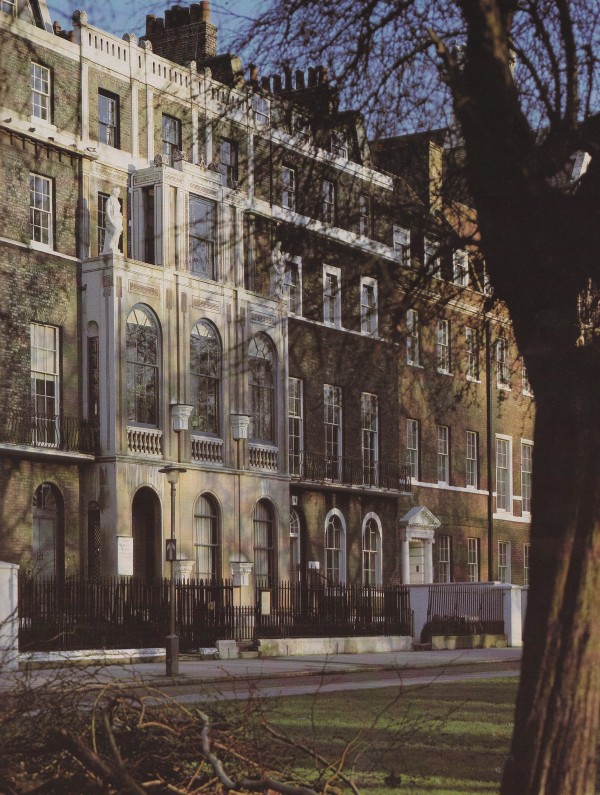

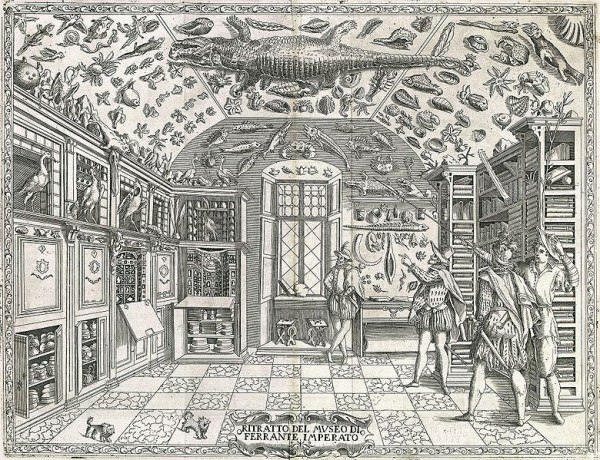

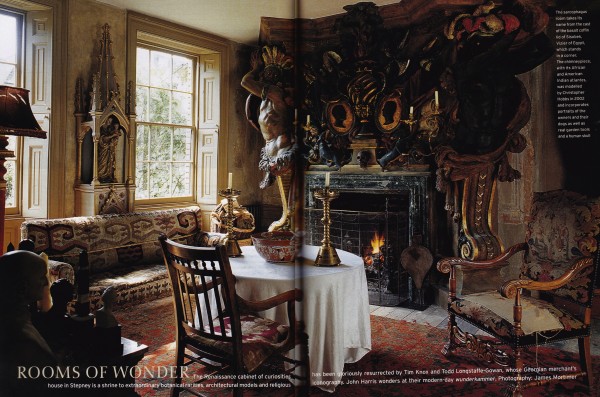

In the fourth installment of Cabinets of Wonder we visit the Sir John Soane House and Museum at 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London, an early 19th-century classical Regency townhouse filled with a rich collection of books, classical antiquities, and works of art. Soane was a voracious intellectual in the vein of Thomas Jefferson. He was particularly passionate about classical Roman architecture having come off the Grand Tour, with a great deal of time spent in Rome after winning the Prix de Rome, where he took delight in studying and measuring monuments, ruins, and architectural fragments. He eventually became the architect of the Bank of England which earned him notoriety and prestigious commissions, making him a very wealthy man in which to indulge his passions.

Soane introduced his mastery of spatial composition and manipulation of light to create mysterious rooms of unique character and depth. It’s not surprising that one of Soane’s good friends was artist J. M. Turner, who later in his career painted only light and the source of light, the sun, in fluid washes of paint – truly the art world’s progenitor of abstraction (He called out on his deathbed “The sun is God!”). Soane, too, was obsessed with light, and throughout his house are cues to this obsession, from looking-glasses to his collection of poetry by Wordsworth, who was also drawn to the mysterious and transformational qualities of light.

Essentially a classicist, Soane was not immune to the spirit of his age and developed a fondness for Romantic Revival styles, in particular Gothic art, shared by his contemporaries. James Kirklington wrote for The World of Interiors “It was Soane’s great contribution to architecture to create a fusion of handed-down styles, reinterpreting the classical language of architecture, investing it with new idioms and enriching its long-established vocabulary.”

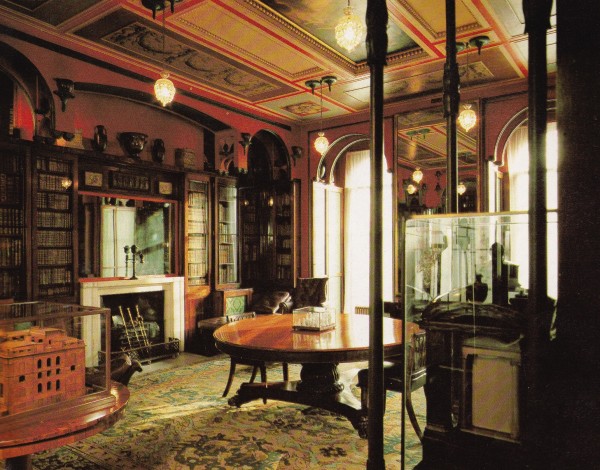

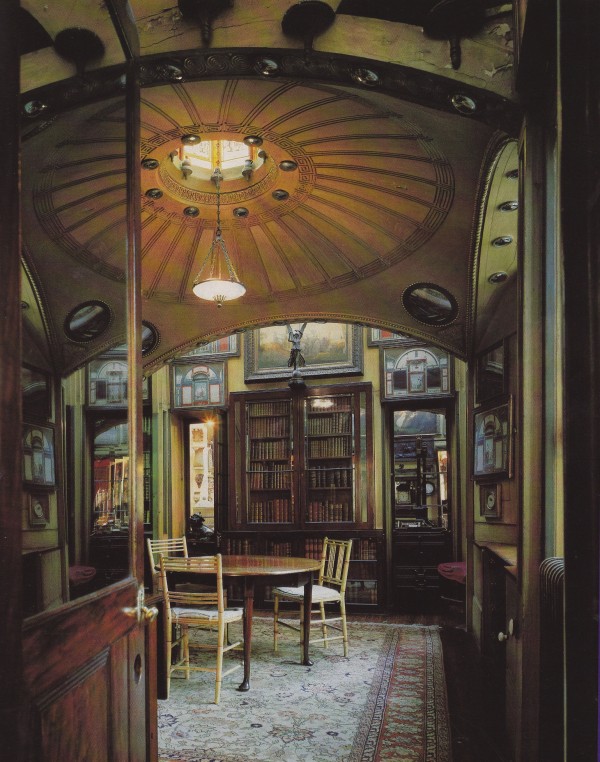

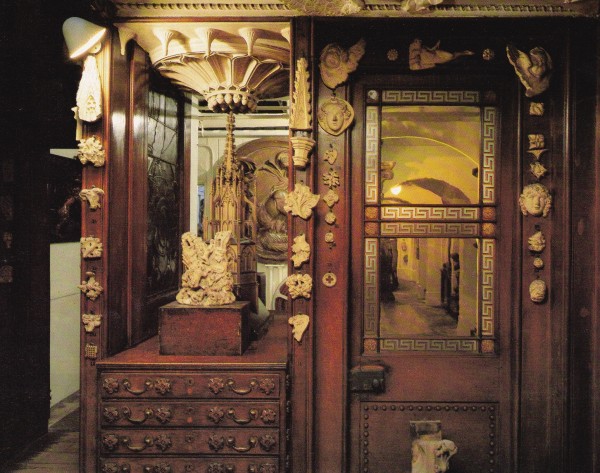

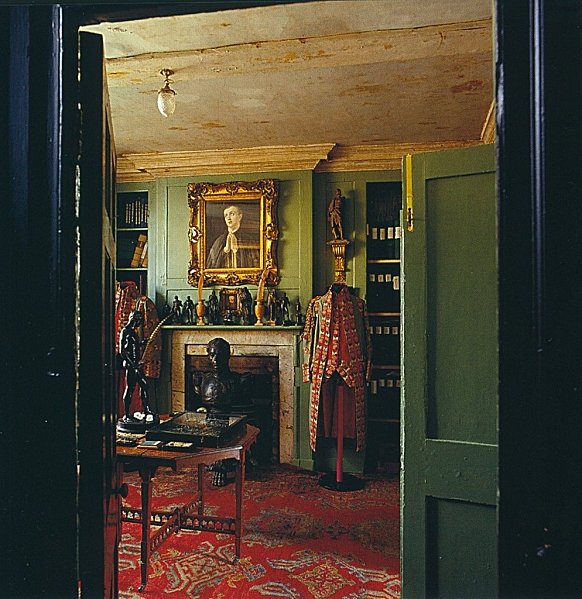

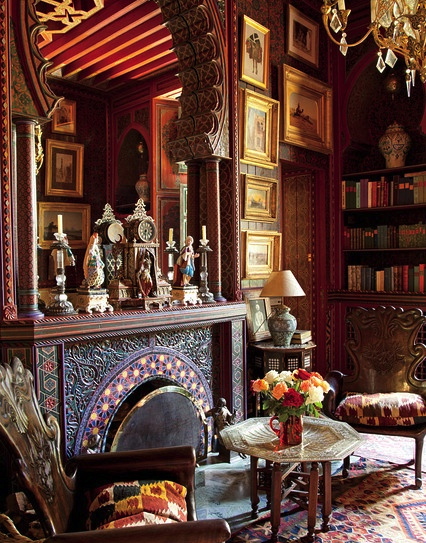

The dining room and library, off the entrance hall, is a tour-de force of layered recesses and arches divided by a canopy supported by two projecting piers formed into facing bookcases, essentially creating one room. The canopy and piers are in the Gothic style, including miniature fan vault brackets supporting statuary and Gothic capitals. A model of Tyringham Hall, built by Soane, rests on a table in the foreground. Pompeian red walls and dark oiled bronze fittings reminiscent of ancient Roman oil lamps is well-suited for a collection of antiquities from Rome and Greece which grace the tops of the book cabinets.

The canopy separating the library and dining room is inset with mirrors to give the illusion that the ceiling is repeated next door.

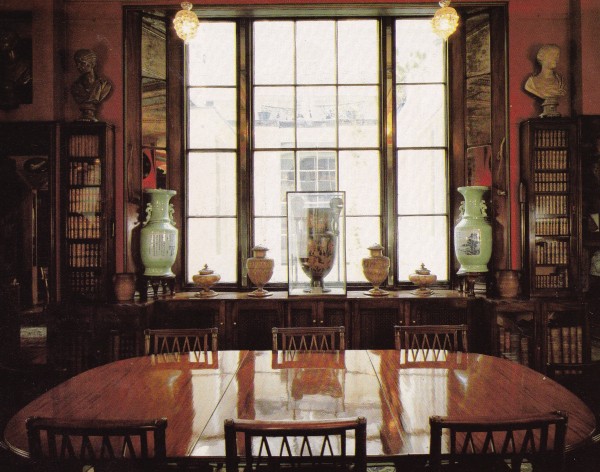

In this view toward the dining room window mirrors in the jambs and mullions are reflected, providing wonderful atmospherics during a candlelit dinner. On the windows ledge is a large Apulian crater, the “Cawdor Vase”.

A view toward the dining room from the library, which looks onto the Monument Yard (an atrium of sorts), in a drawing by architect and artist Karl Freiderich Schinkel.

A view toward one of four large looking-glasses reflecting back an enhanced view of the dining room.

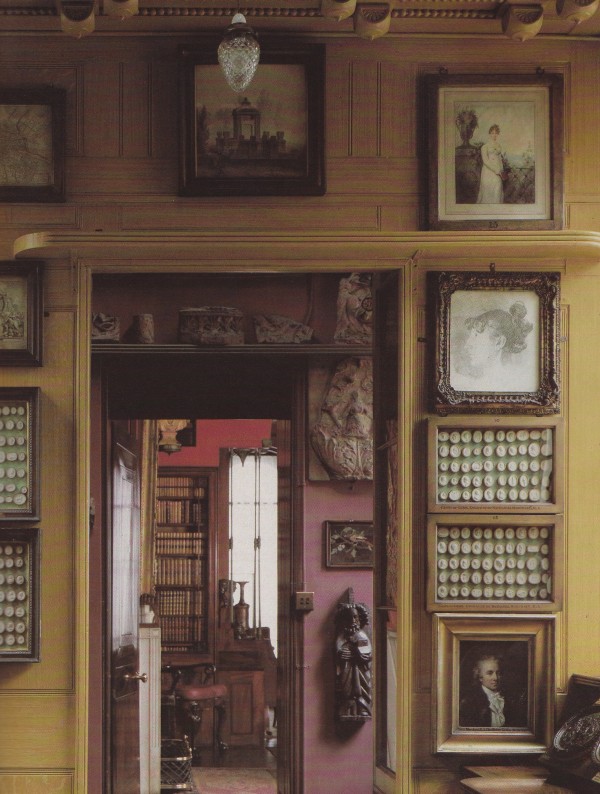

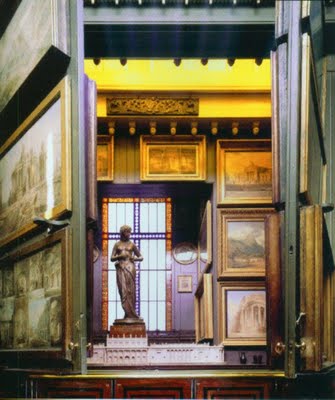

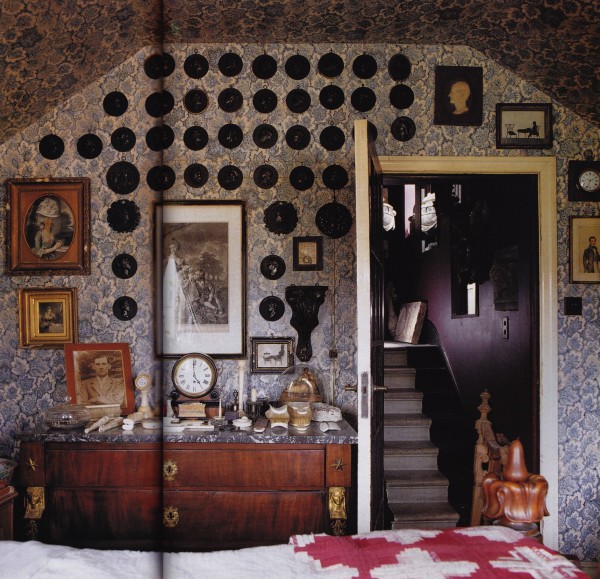

Around the door of Soane’s dressing room leading to the study are stacked portraits and plaster casts.

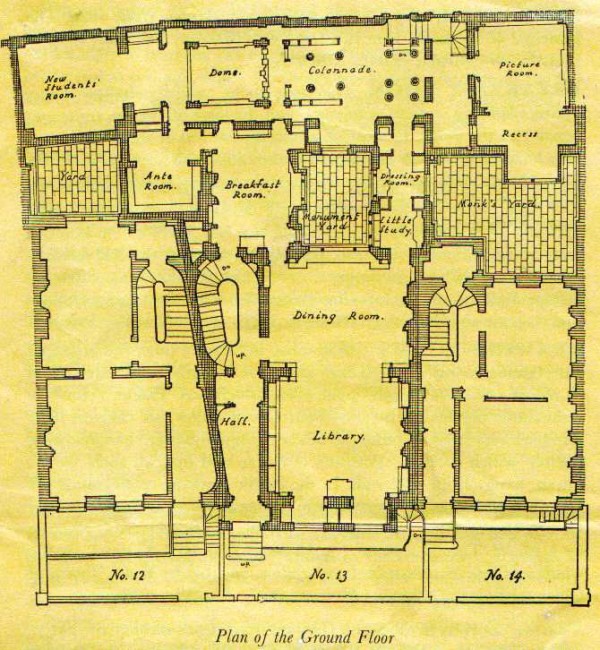

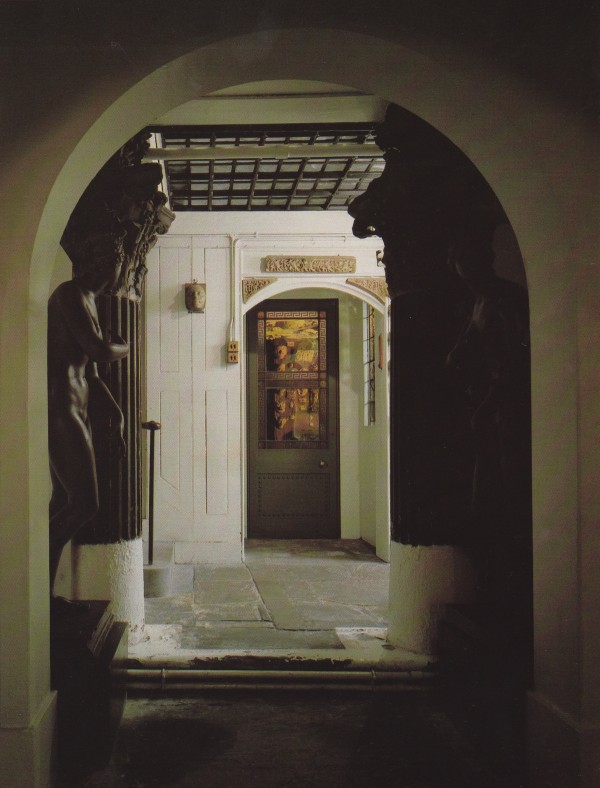

The John Soane house comprises three narrow, vertical townhouses which were renovated with a new floor plan. From the dining-room-library at the front of the house one passes through a succession of small rooms aglow with lanterns and reflecting mirrors and miniature antiques ranging from marble fragments brought back from Imperial Roman villas to German bronze statuettes of the early 17th-century.

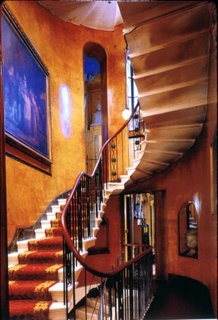

Guests pass the elegant cantilevered stone staircase towards the back of the house into the next room, the Breakfast Parlor.

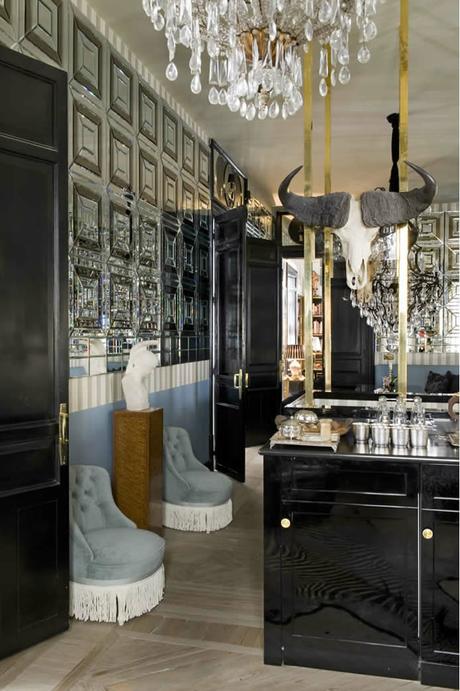

The Breakfast Parlor is Soane’s crowing achievement, proffering his alchemical deftness at harnessing and refracting light and incorporating ingenious spatial solutions within a relatively small room. A shallow dropped pendentive dome – like a decorative plaster tarpaulin – is punctuated by a central oculus and framed with looking-glasses at the dome’s edge that reflect and create mysterious sources of light and vistas. Flanking the dome are light-wells, adding to the heightened sense of drama and atmospherics. An octagonal lantern in the dome with scriptural subjects painted on its glass illuminates the room’s center.

A detail of the Breakfast Parlor’s spherical ceiling, with small looking-glasses in the soffits and large ones in the pendentive. Of this room Soane commented, “The views … into the Monument Court and into the Museum, the mirrors in the ceiling and the looking-glasses, combined with the variety of design and decoration of this limited space, present a succession of those fanciful effects which constitute the poetry of architecture.”

Soane threw parties in the Sepulchral Chamber for three days to celebrate his winning bid for the sarcophagus of King Seti I. From the ‘Illustrated London News’ in 1864.

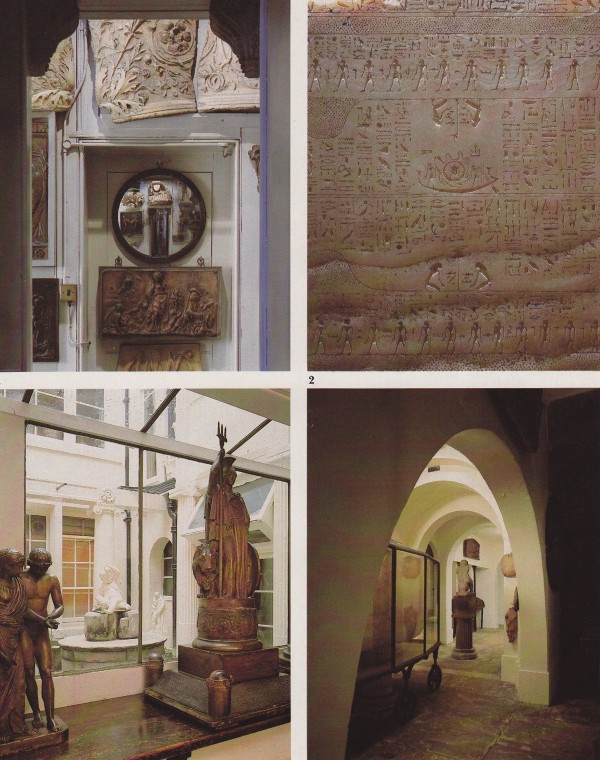

Soane’s house would not only become a repository of Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquity, but also home as laboratory, school, office and museum. The Sarcophagus Room of 1864 was created around the Sarcophagus of Egyptian King Seti I, from the Valley of the Kings, first discovered in 1825. Soane devised a glazed dome on the ground floor to illuminate the Sepulchral Chamber one floor down in the “catacombs”, where the sarcophagus takes pride of place at center, the chamber’s walls lined with archaeological fragments. Regarded as one of the most important archeological discoveries in Egypt, Soane managed to outbid the British Museum and make it his own.

The ancient Egyptian sarcophagus of King Seti I, dating back to 1279 B.C., in the “catacombs” of the subterranean floor. Photo by Derry Moore.

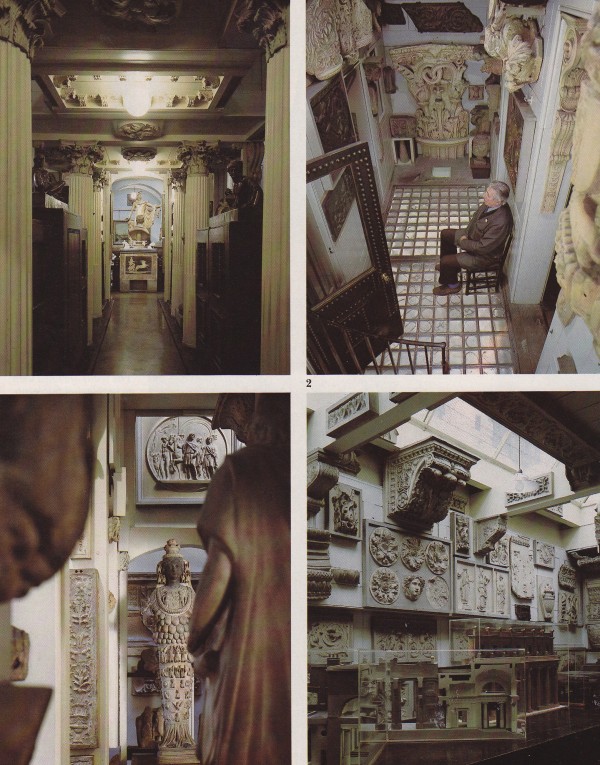

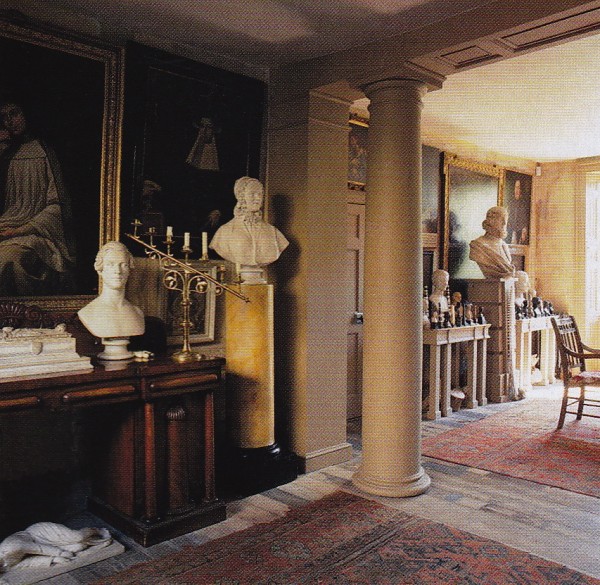

Directly above the crypt on the ground floor is the colonnade capped by a glazed dome. At left is a cast of the Apollo Belvedere on the dome’s balustrade. The walls are lined with archaeological fragments. Photo by Richard Bryant.

Beneath the dome is the Sepulchral Chamber which leads to the crypt. A bust of Soane by Sir Francis Chantrey, flanked by statuettes of Michelangelo and Raphael by John Flaxman, surveys the sarcophagus of Seti I. Photo by Richard Bryant.

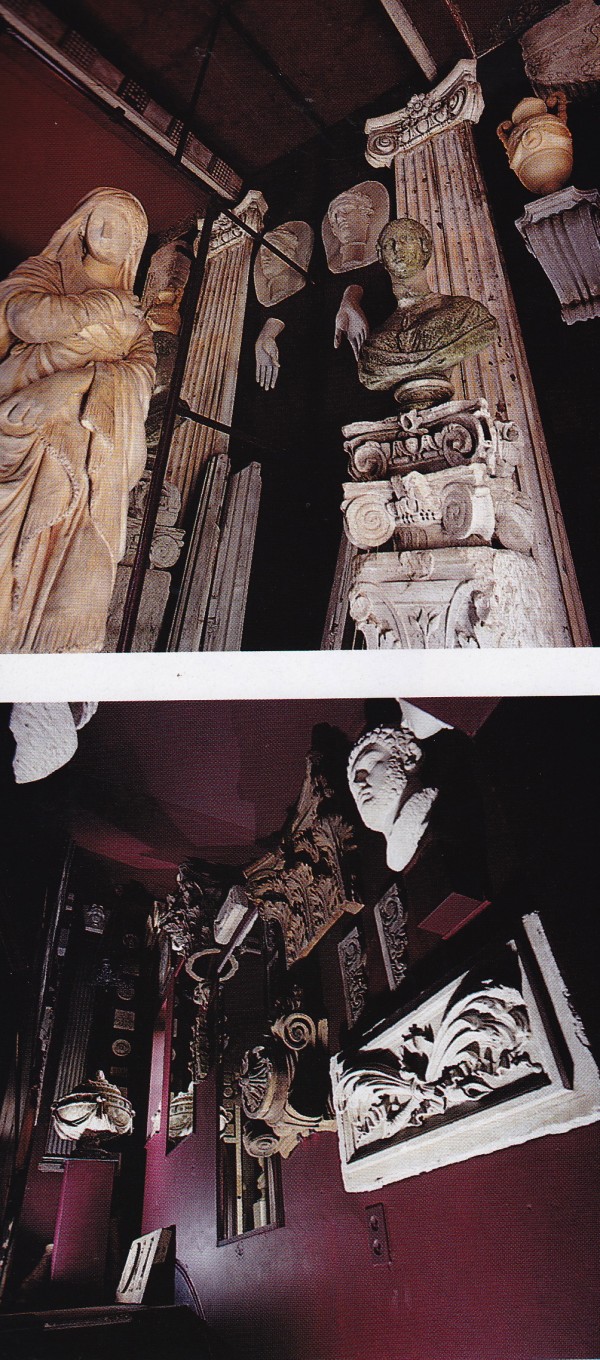

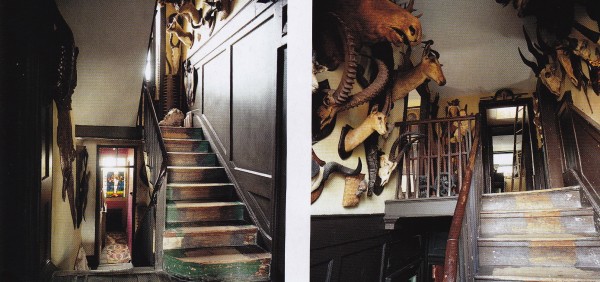

The “catacombs” in the house’s dark underbelly, dominated by the Monk’s Parlor, above, satisfied Soane’s love affair with Gothic art and literature. It faces the crypt and offers a view out a window to the Monk’s Tomb, a version of faux-medievalsim beloved by the Romantics.

In the subterranean world of the “catacombs”, above, we are looking at the other side of the Monk’s Parlor’s door. To its left and right are casts of the Venus di Medici and the Venus at the Bath. The Corinthian columns are from Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli.

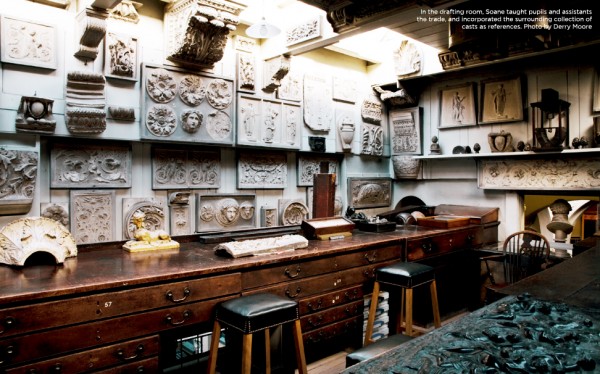

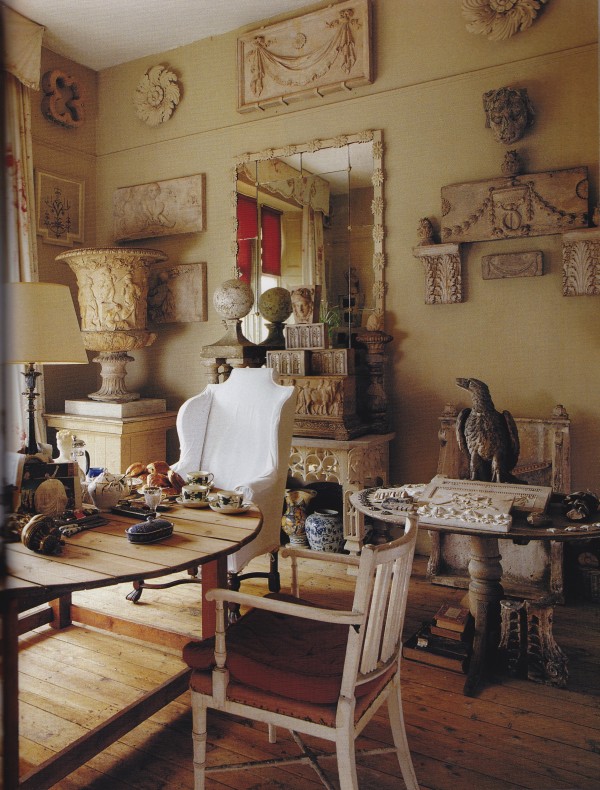

One level up on the ground floor is the Student’s Room, where Soane would instruct his pupils on architectural classifications. It is supported by rows of miniature Corinthian columns which, in turn, form a colonnaded passageway to the domed gallery featured earlier.

Clockwise from top left: the colonnade supports of the Student’s Room. On the tops of its cupboards are restored models of recumbent figures from the Elgin marbles. Next, the passage leading to the Student’s Room has a glass block floor which illuminates the Monk’s Parlor below. In the Student’s Room Roman and Renaissance casts hang over models of Soane’s projects. Last, the statue of Aesculupius stands in the colonnade, a Roman version of a Greek original.

Beyond the dome and colonnade on the east side of the ground floor is the Picture Gallery, famous for its collection of oil paintings by Hogarth, Caneletto Turner, and Raphael, as well as for its intergration of Gothic and classical architectural themes.

Masterfully rendered hinged double panels swing open to reveal more layers of paintings, which ultimately open to reveal the Shakespeare Recess, a small shrine devoted to the memory of the great writer.

Up again to the first floor (the second floor in America) we come to the sunny South and North Drawing rooms.

At the end of the South Drawing Room a bookcase is filled with manuscripts and books by Soane, topped by a bust of Palladio. Soane’s solution for masking intrusions from a neighbor’s adjoining house was an elegant curved wall.

Double doors from the South Drawing Room lead into the North Drawing Room where cabinets contain architectural models and drawings by Soane’s master instructor and employer, George Dance, who discovered Soane’s talent and provided him with a scholarship to study in Rome.

The narrow glazed loggia allows light into the South Drawing Room where a bank of windows once existed.

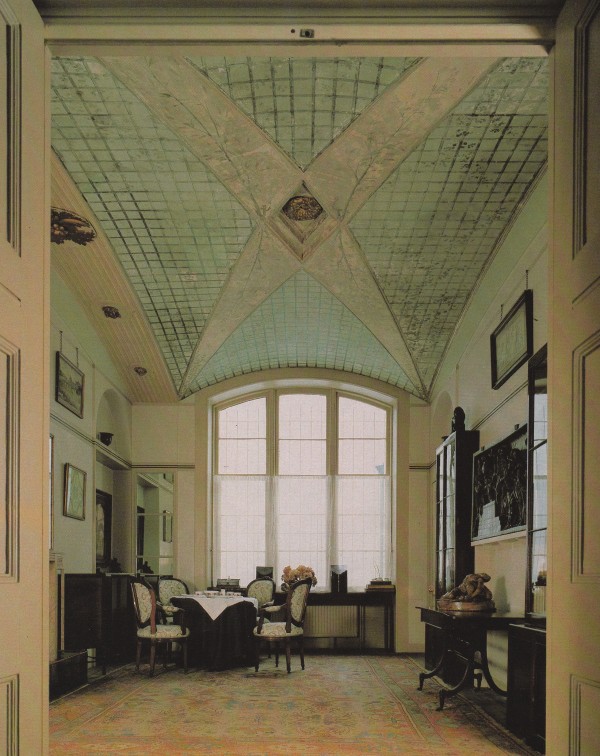

Pictured above is the Breakfast Room at no. 12 Lincoln’s Inn Fields that Soane designed and lived in while renovating no. 13.

Entering into the world of Sir John Soane is akin to entering a virtual Regency cabinet of wonder: for nearly two-hundred years every aspect of his Classical-Romantic Revival interiors have gone unchanged, as directed by Soane in his will upon his death in 1837. For many years it stood neglected as adherents of the Aesthetic, Arts and Crafts, Gothic and Art Nouveau movements shunned Soane’s classical purity. It wasn’t until the 1950’s, when a young Philip Johnson referenced Soane’s library-dining-room for a guesthouse on his Glass House property in New Canaan, Connecticut, that Soane’s name and body of work re-entered the lexicon of contemporary architecture. Johnson’s reductive reference to Soaneian classicism would soon illicit interest in other young architects of that era, such as Robert A. M. Stern and Michael Graves, to name but two – proponents of a new, modern direction in architecture which embraced a potpourri of classical and Romantic revival styles that would come to be classified as Post-Modernism in the years ahead.

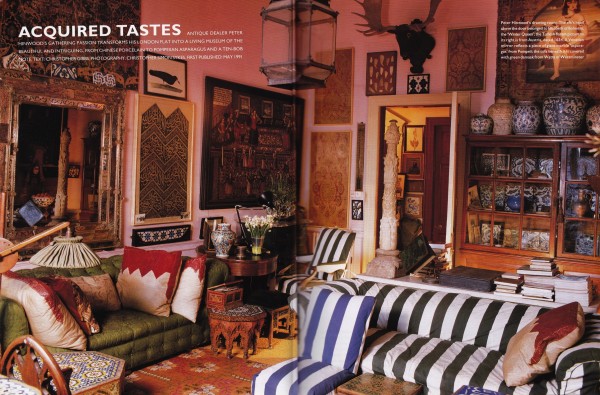

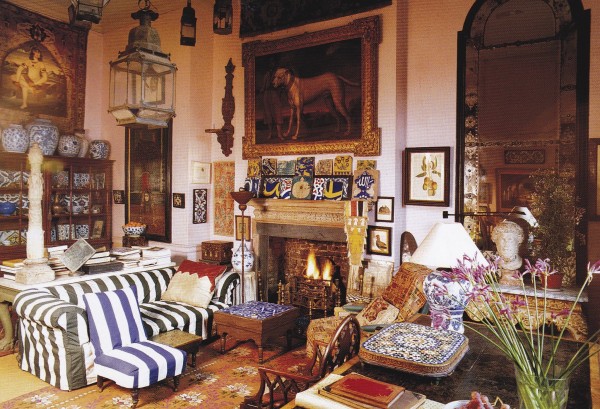

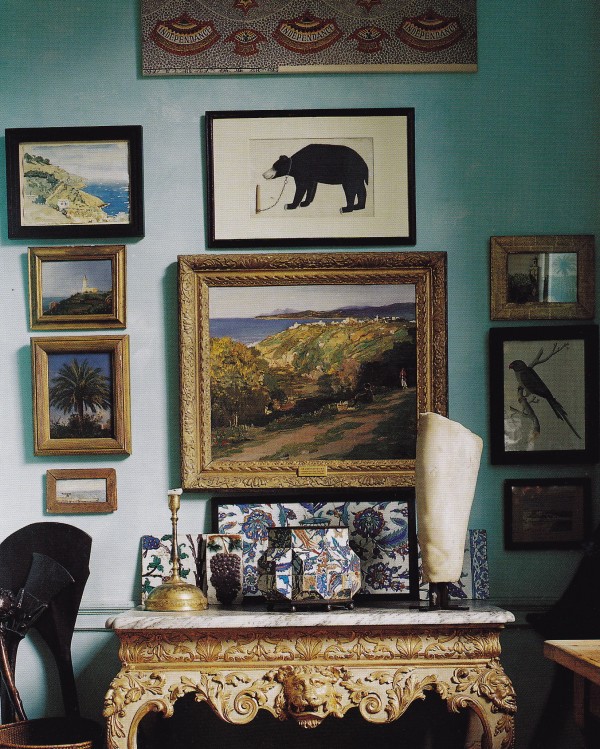

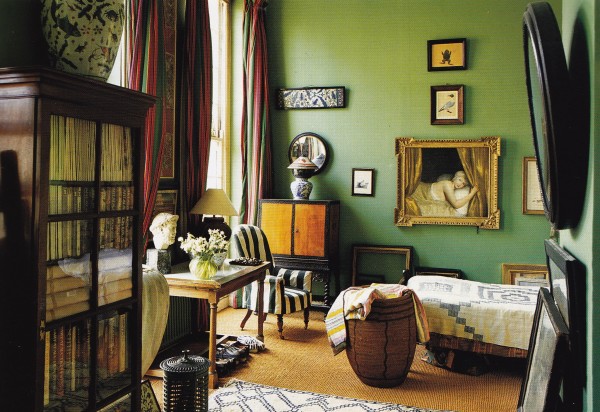

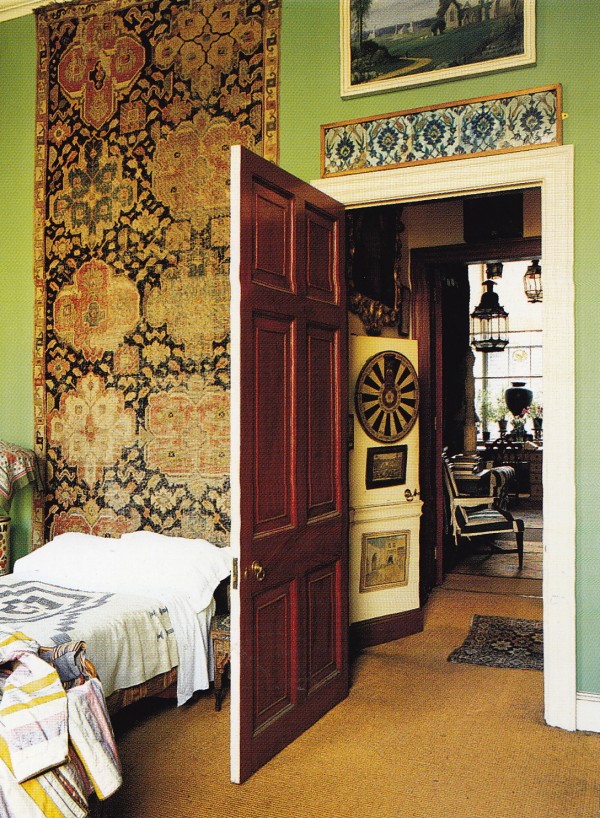

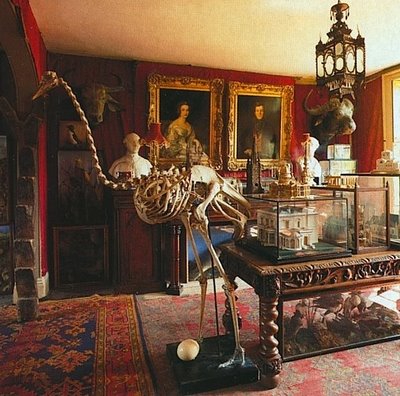

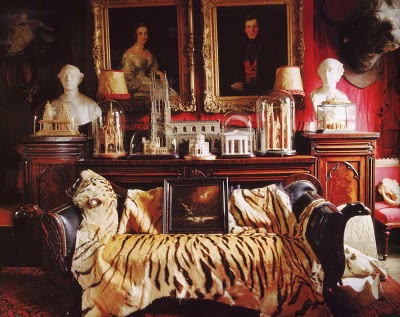

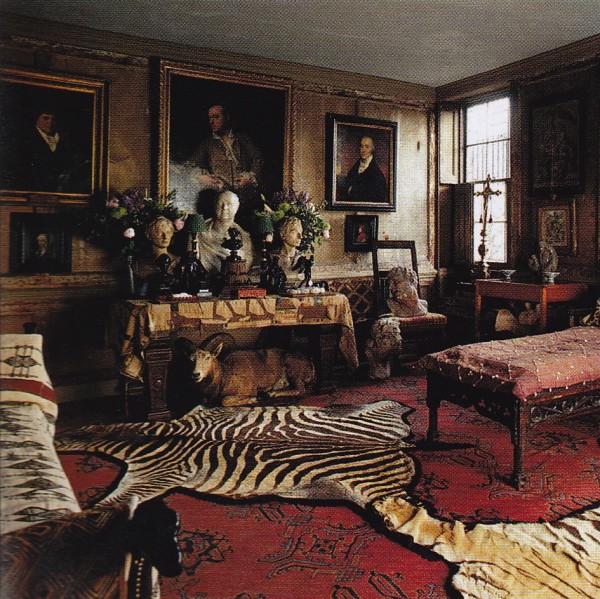

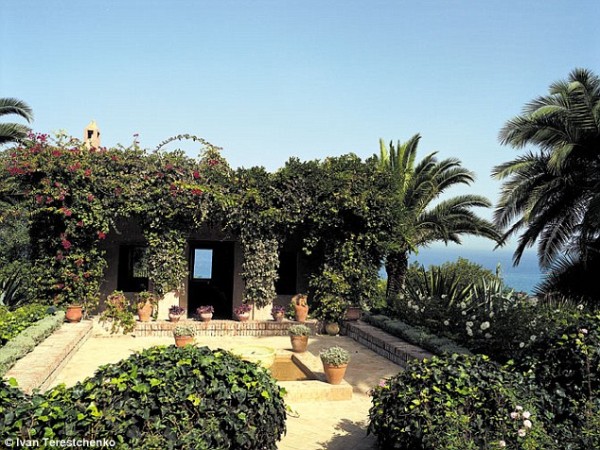

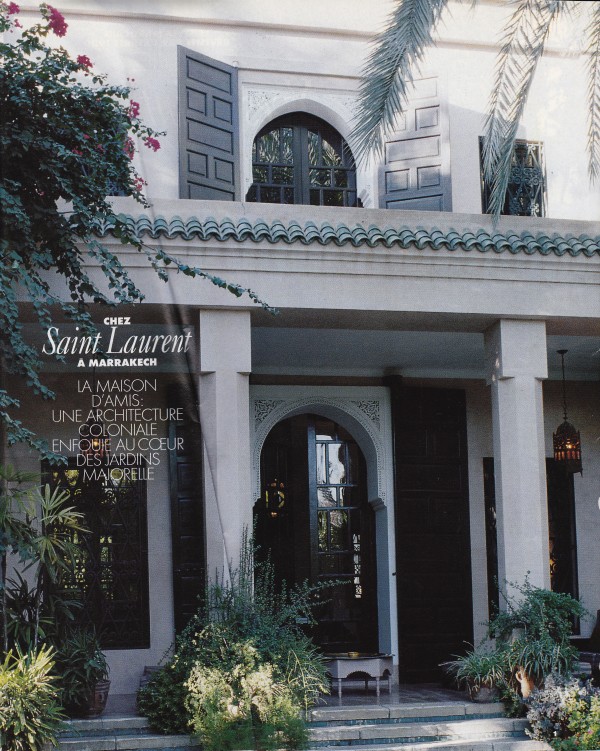

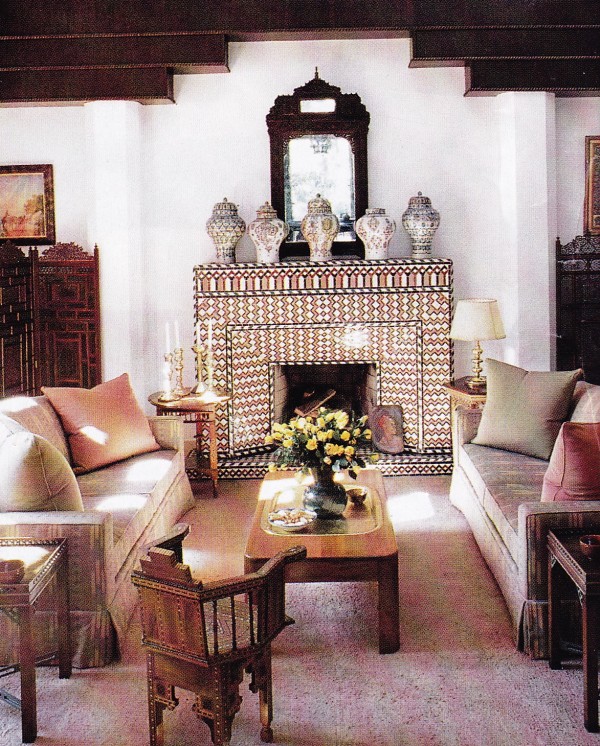

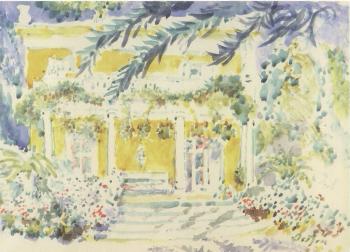

In the fifth, and last, installment of Cabinets of Wonder we will visit the Milan apartment of author Umberto Pasti and his partner, fashion designer Stefan Janson.

Content based on an article written by James Kirklington for The World of Interiors, April, 1982. Photos from this issue by Richard Bryant.