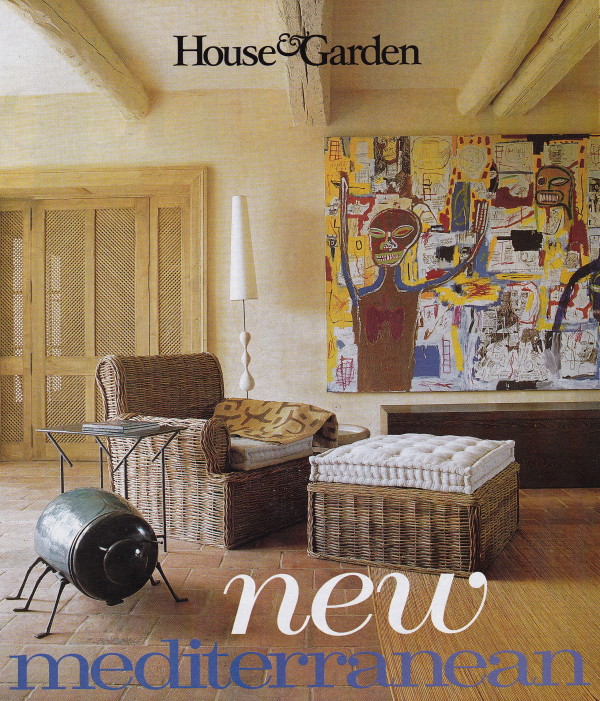

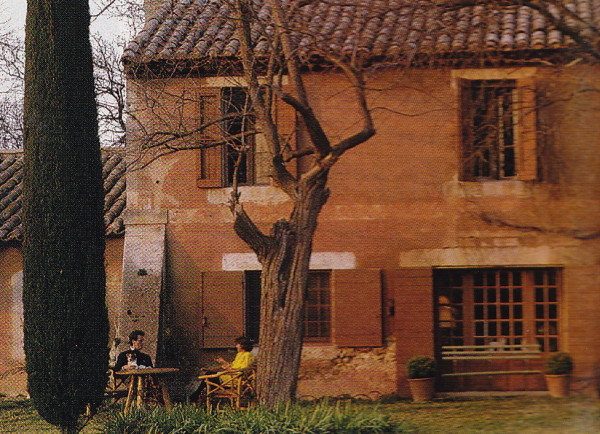

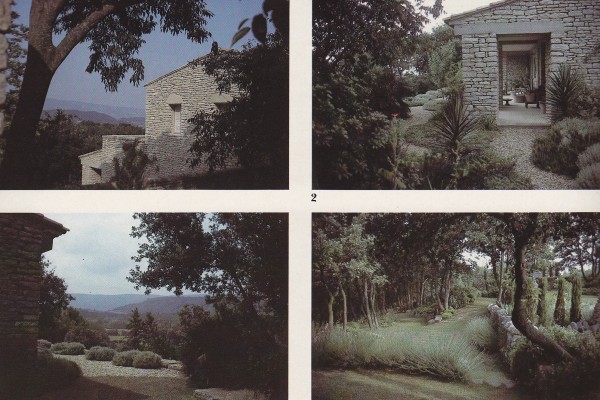

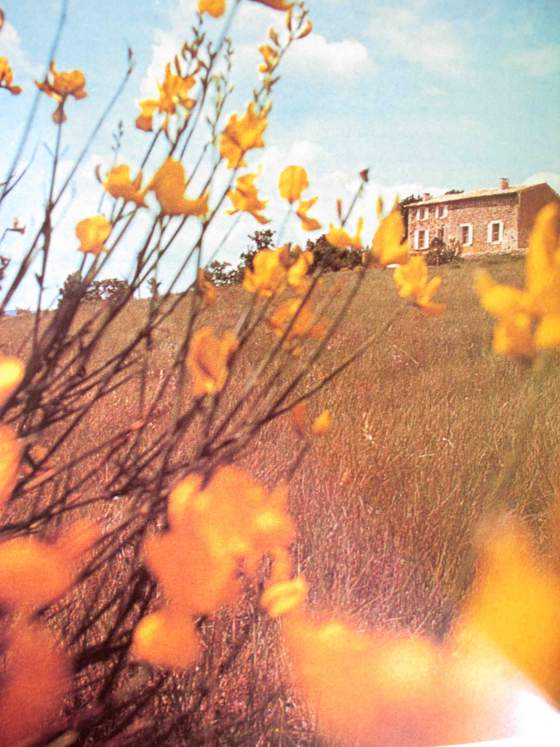

Toujours Provence continues, bringing us to Betty and François Catroux’s 16th-century farmhouse, Les Ramades, in the Luberon. Imagine escaping here from Paris, approaching the property through apricot groves to a dead-end road lined with plane trees, where you then enter the intimate and highly stylish world of the Catroux’s. The approach only hints at what’s to come, as bits and pieces reveal themselves, culminating with the Provençal stone main structure built in the 14th-century with later additions made in the 16th-century – all enveloped by lushly landscaped gardens and organic fortress-like walls promising utmost privilege and privacy. Our tour begins with photos taken for Architectural Digest, French Elle Decor and British House and Garden in the early 1990’s followed by recent photos featured in The Wall Street Journal’s on-line edition.

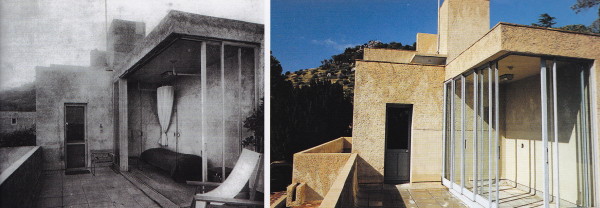

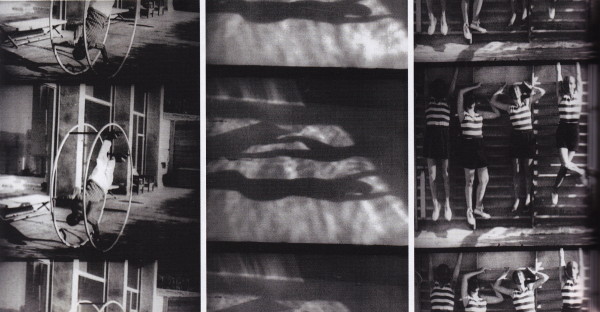

A lush stillness comes over the property with views of the Luberon Massif beyond the fountain and swimming pool – one of several intimate “outdoor rooms” created, framed here by a pool house and changing rooms.

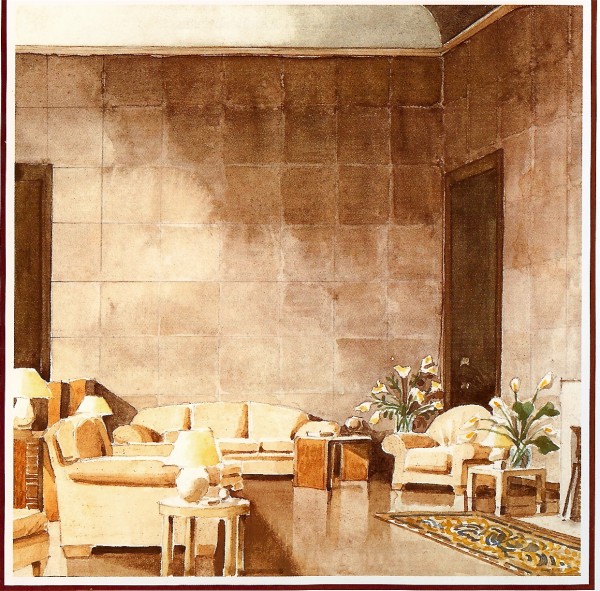

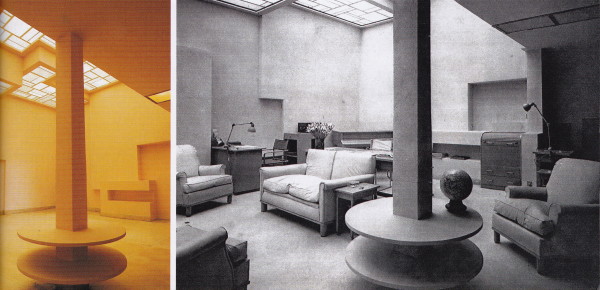

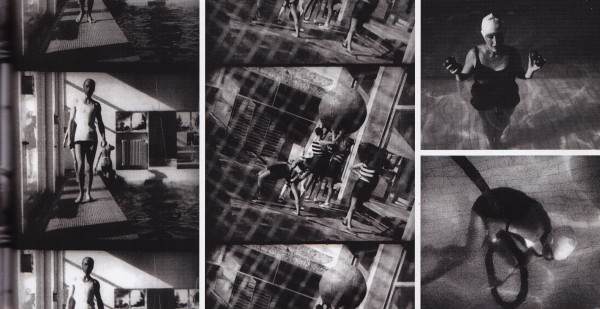

In this photo taken in the early 1990’s spare elegance informs a living area with rustic simplicity. A cement floor with a diamond pattern created with imbedded river stones is reminiscent of a Moroccan rug. The monochromatic color scheme allows form and texture to create visual interest while black accents define space with line and pattern. The gridded pattern of the lanterns hung above the sofa stand in for art.

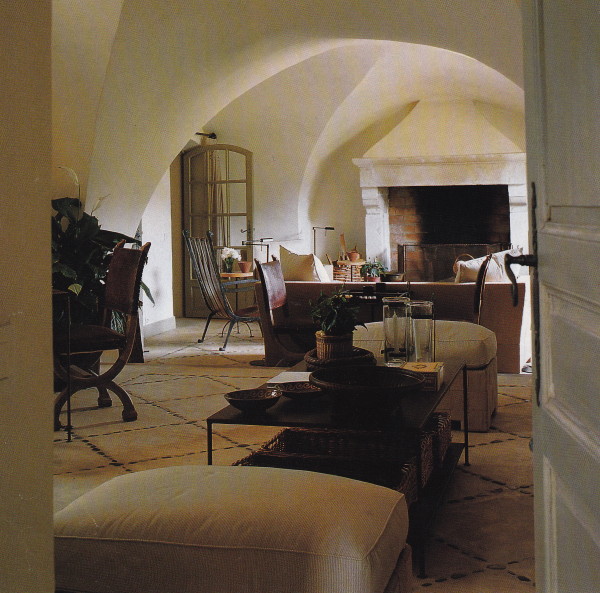

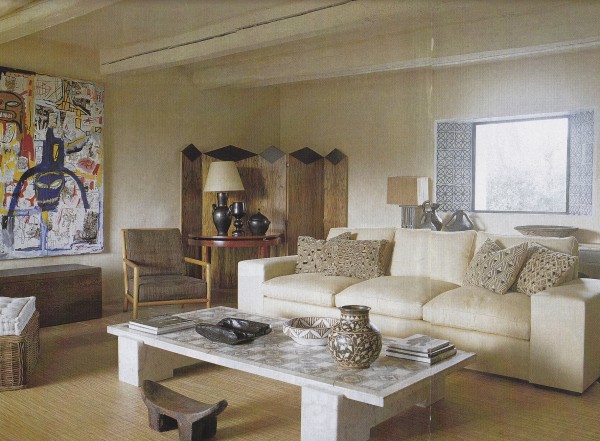

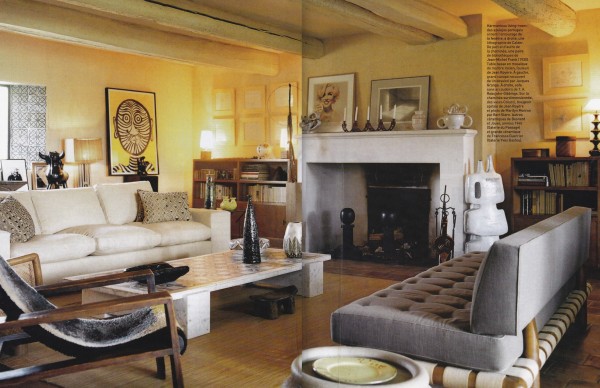

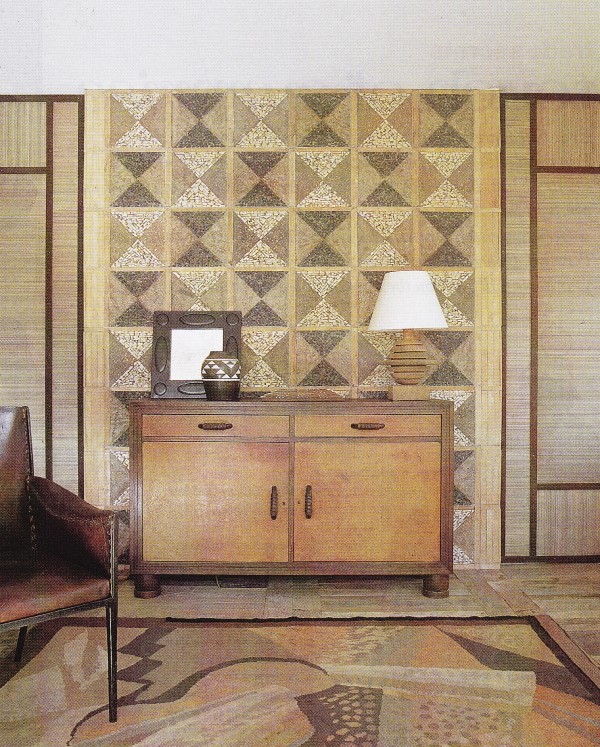

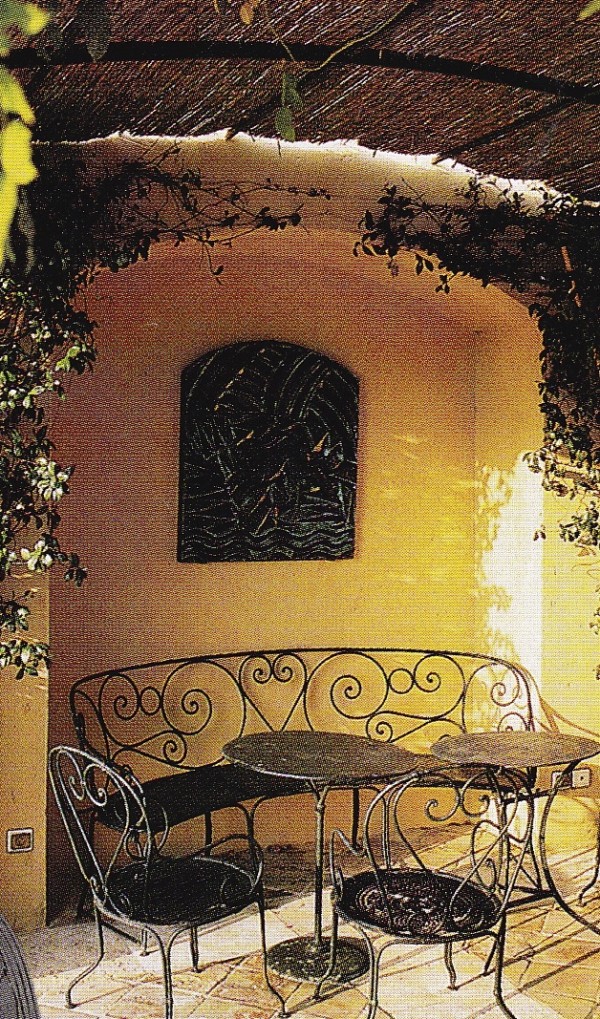

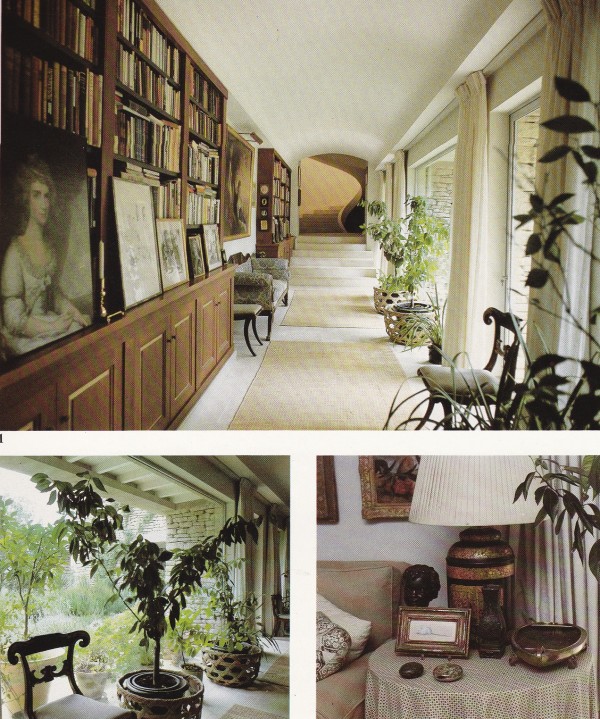

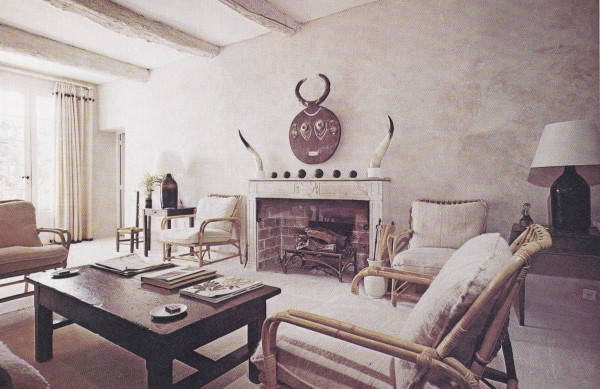

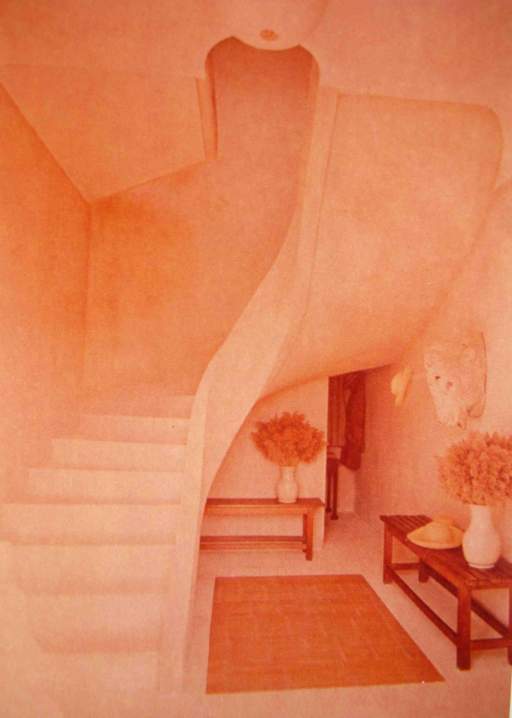

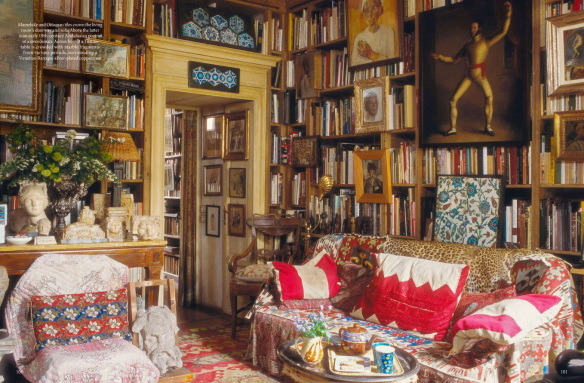

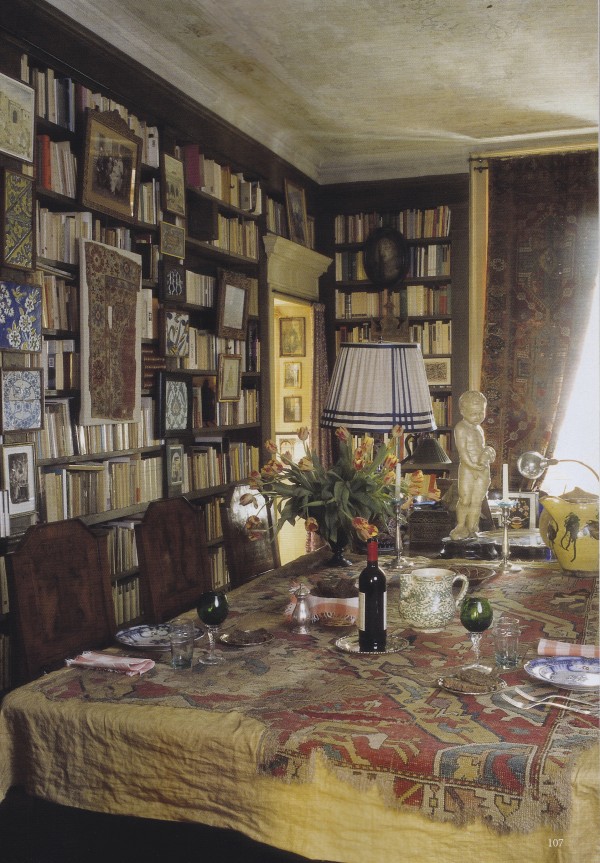

A series of vaulted salons are original to the house, its plaster in the most perfect and discreet shade of parchment. Natural materials – cotton, linen, leather, wood and iron – commingle to create effortless informality in rooms of near monastic simplicity.

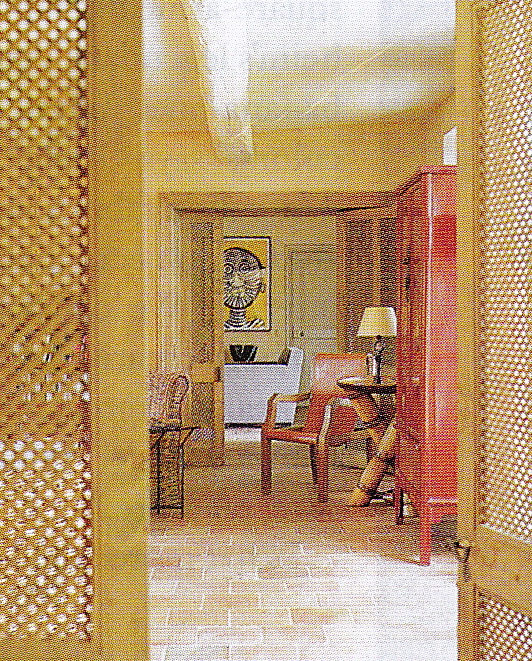

A view into one of the vaulted salons with a games table for two set behind a sofa. There is a subtle yin-yang quality to these spaces: here, the curving shapes of the chairs mimic the curves of the walls while the cubic upholstered furniture compliments the diamond-patterned floor.

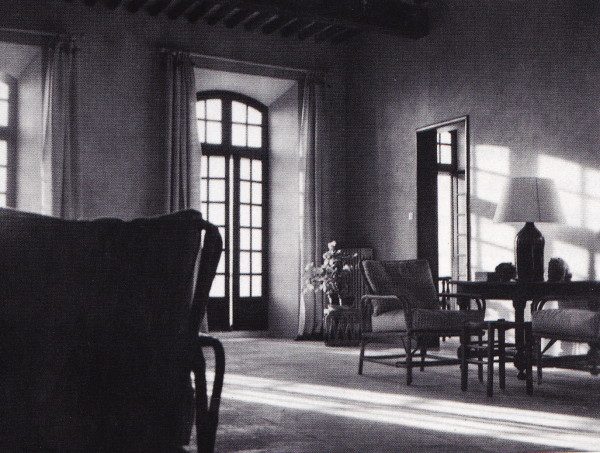

Another games table is placed before French windows in a salon with the same covetable chairs as featured in the previous photo. An amusing lamp that would likely not grab my attention in an other environment appears right at home, adding a touch of insouciant humor.

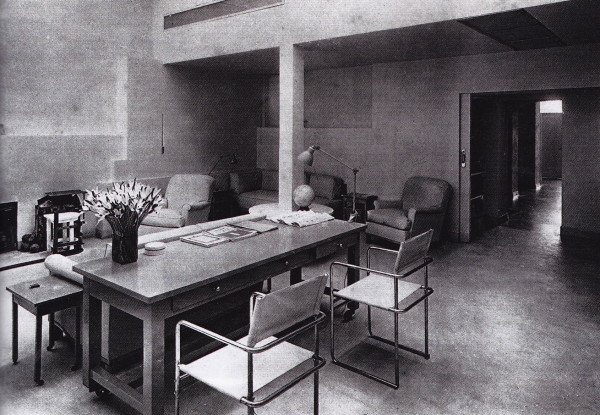

In another view of the barrel-vaulted salons a gutsy forged iron-and-leather campaign-style chair contrasts the sleek minimalism of a Warren Platner lounge chair directly behind it in the adjoining salon. A continuum of harmony exists between color and materials.

In a slightly later view taken of the salon with its games table set for two Catroux has added rough-hewn wood panel screens adjoined with rope configured into an x-design to flank either side of the fireplace. Signs of daily life have also emerged – a now dated television, candle pots on the mantle, and fresh flowers.

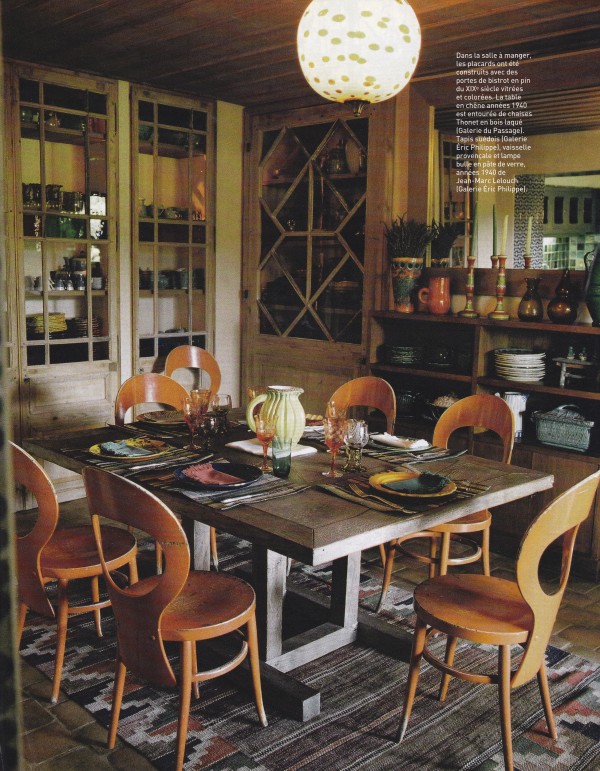

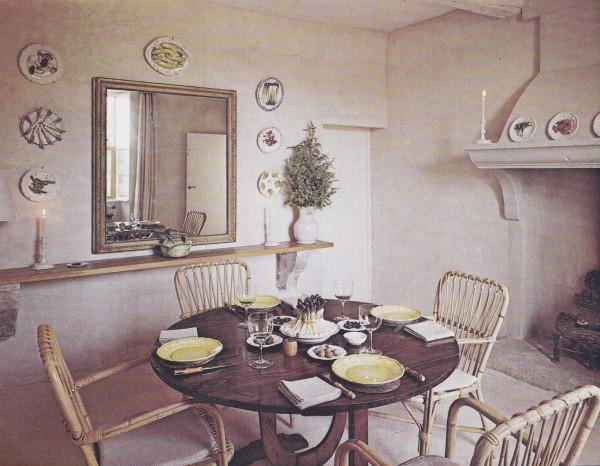

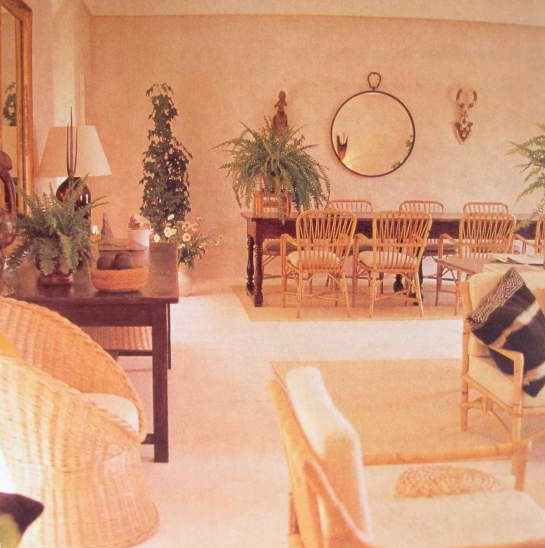

Pale white-washed rough-hewn wood and wicker compliments the rusticity of the painted and scrubbed wood beams in the dining lounge.

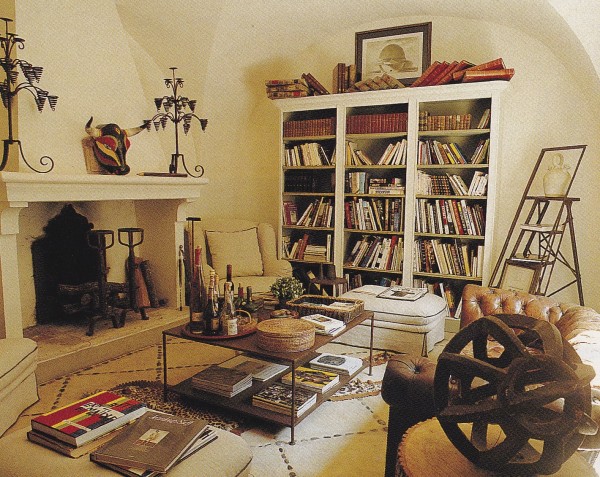

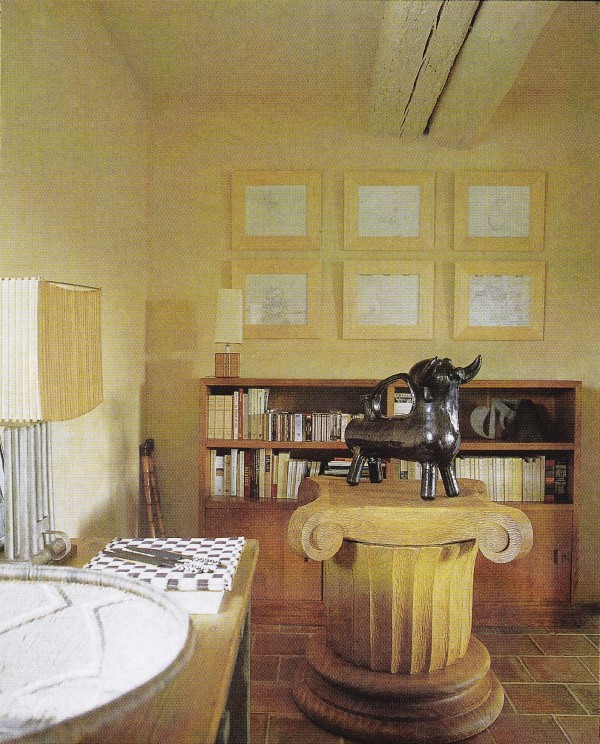

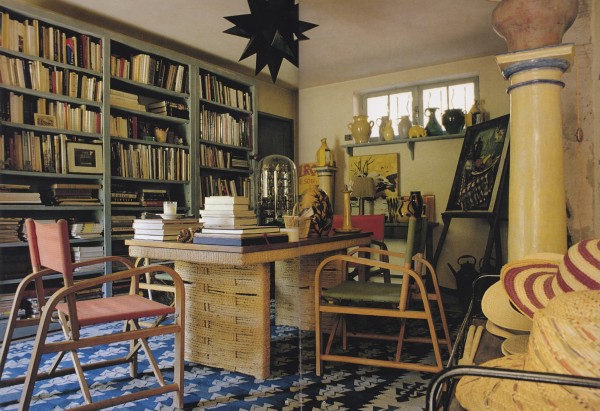

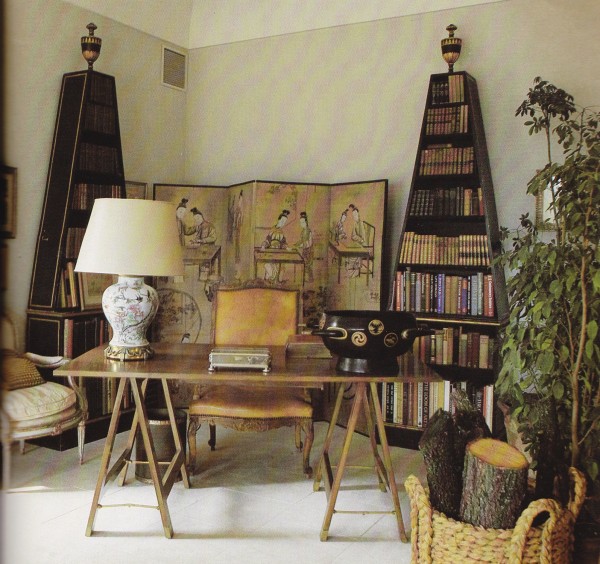

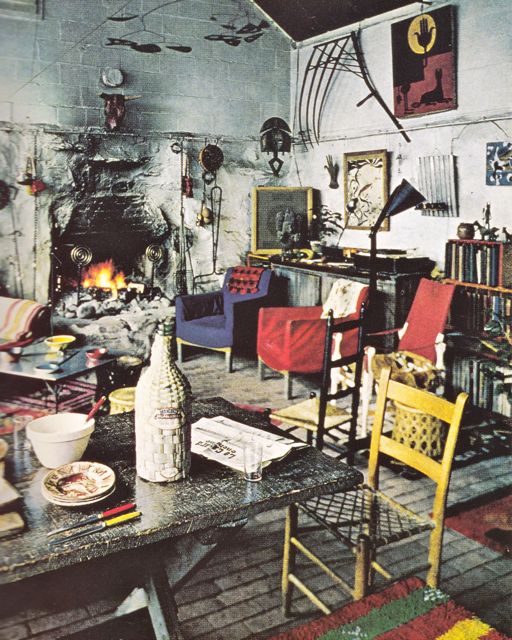

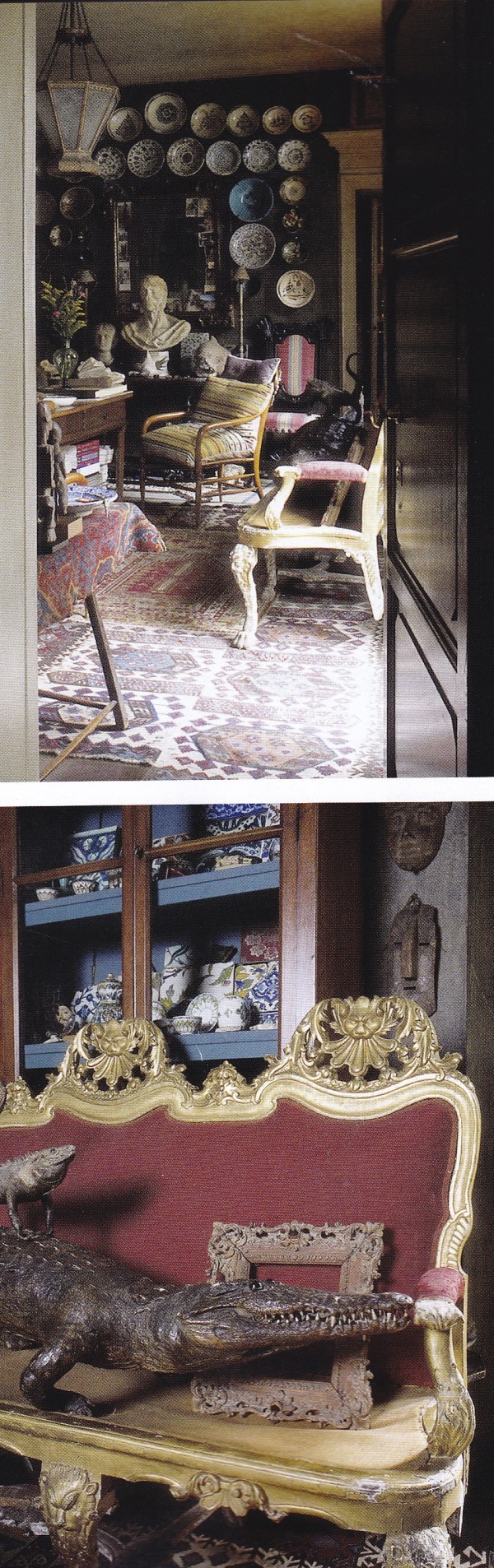

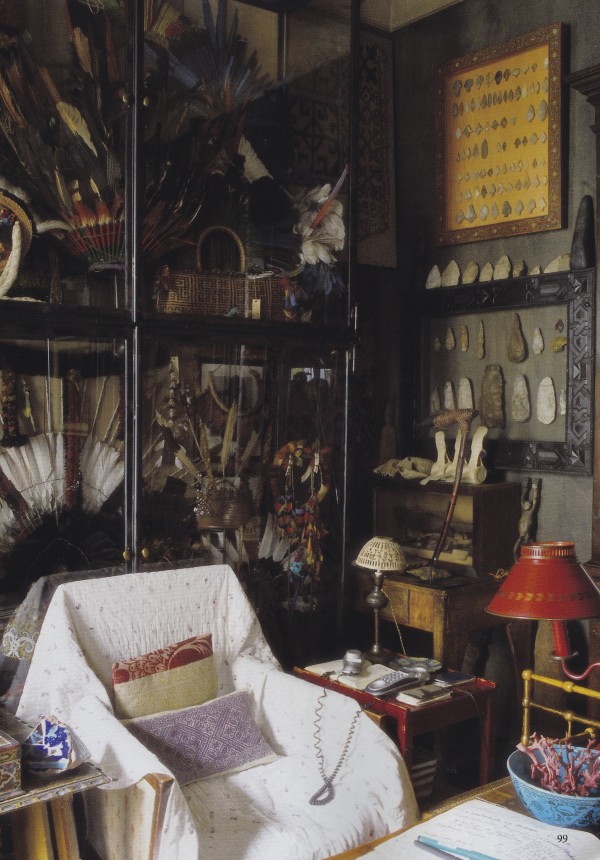

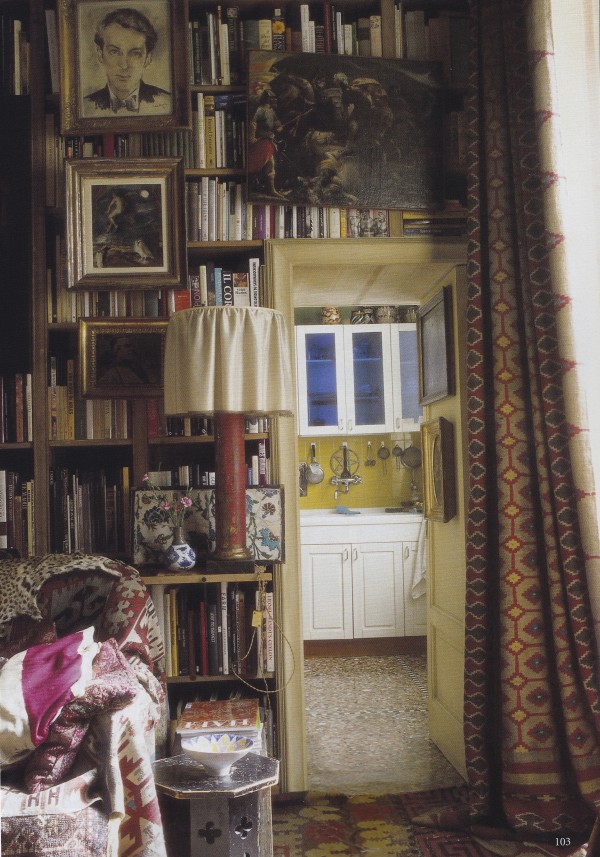

A more collected look informs the library where a tawny English tufted leather sofa, industrial objet d’arts, a bull’s mask from the Camargue and piles of books mix together to create a personal point of view. The black-piped slip-covers reinforce the diamond pattern of the floor design.

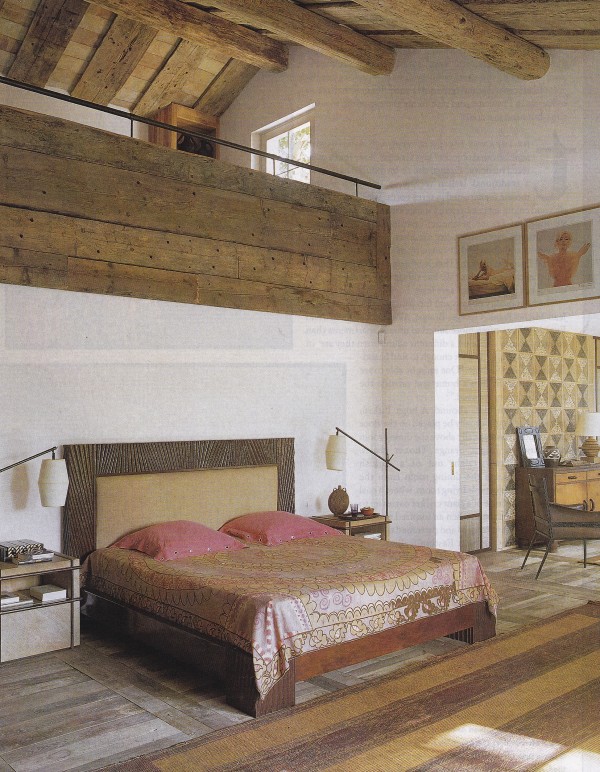

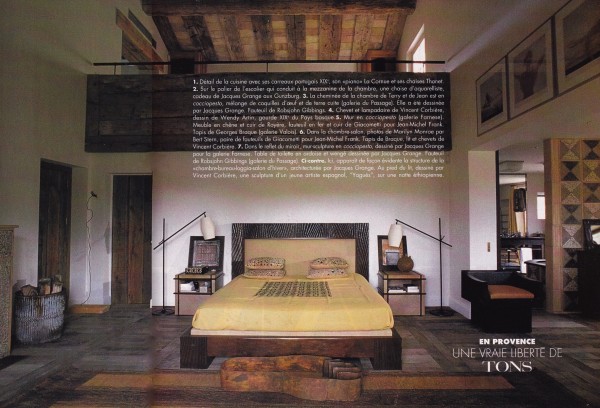

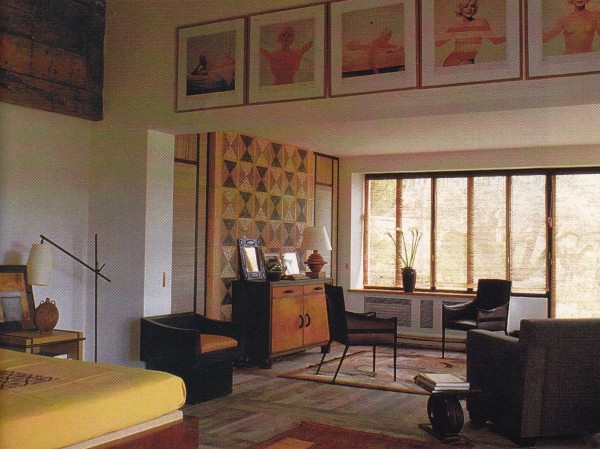

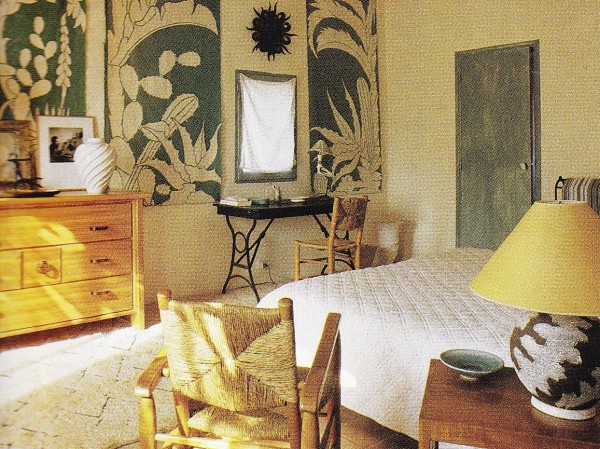

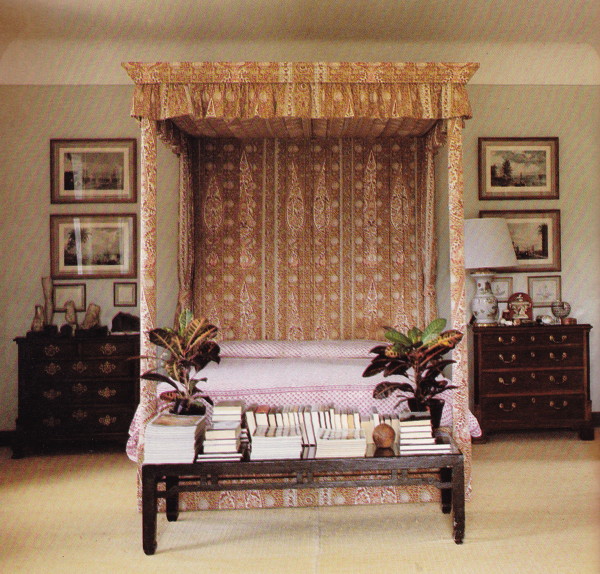

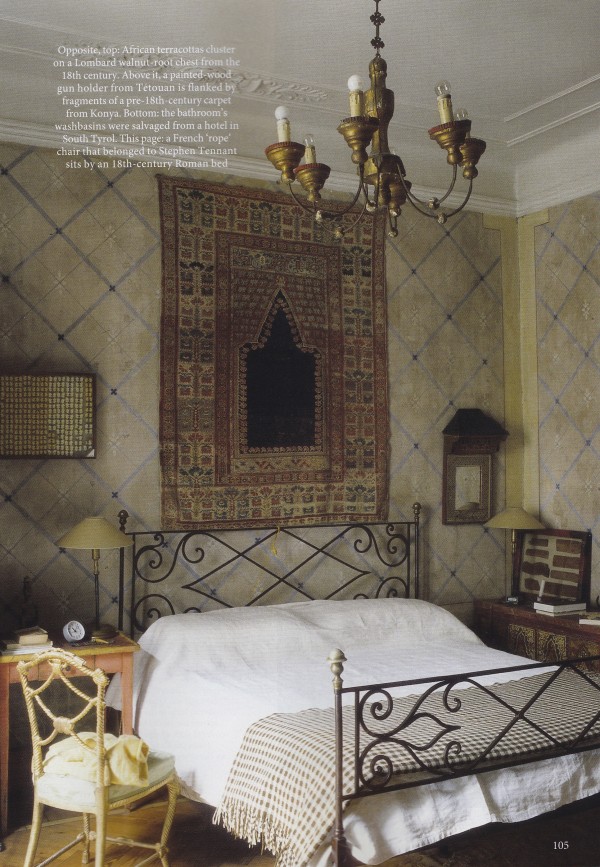

A taste for exotic eclecticism pervades the master bedroom where a papier-mâché throne and ottoman by French artist Isabelle Sig, a 1940 African-style table, and printed Indian fabric for the bed create visual interest.

An alternate view of the whimsical and casually draped master bed.

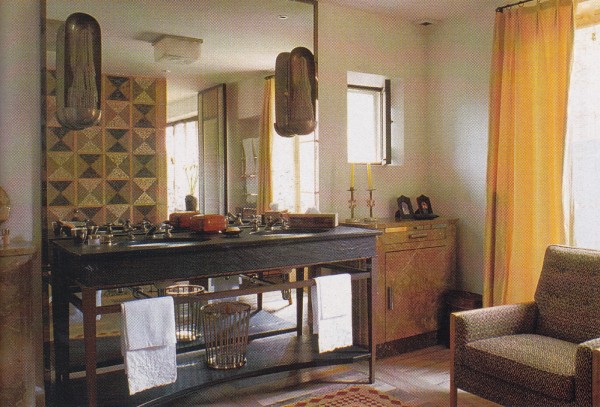

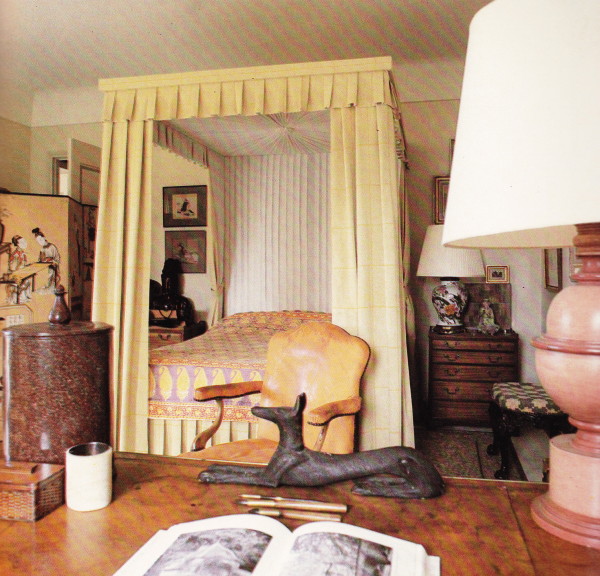

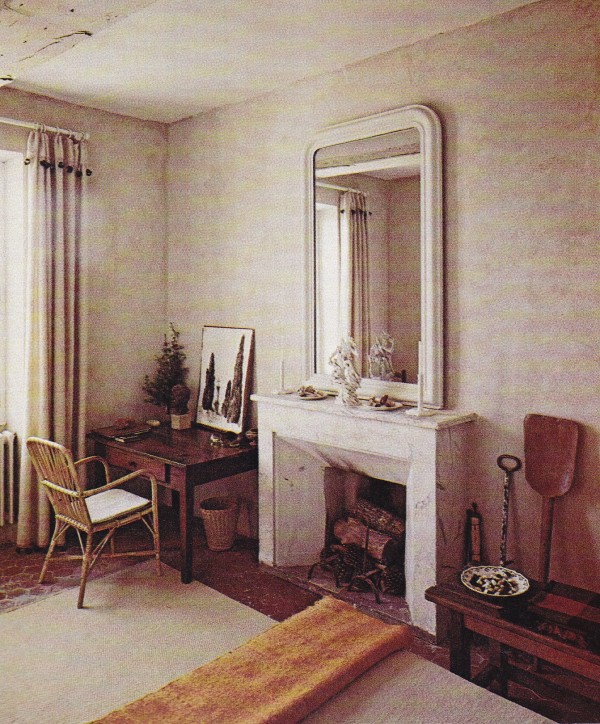

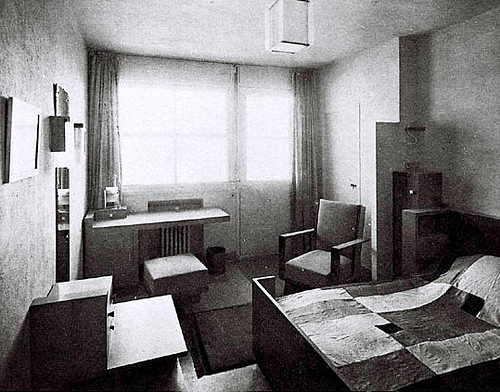

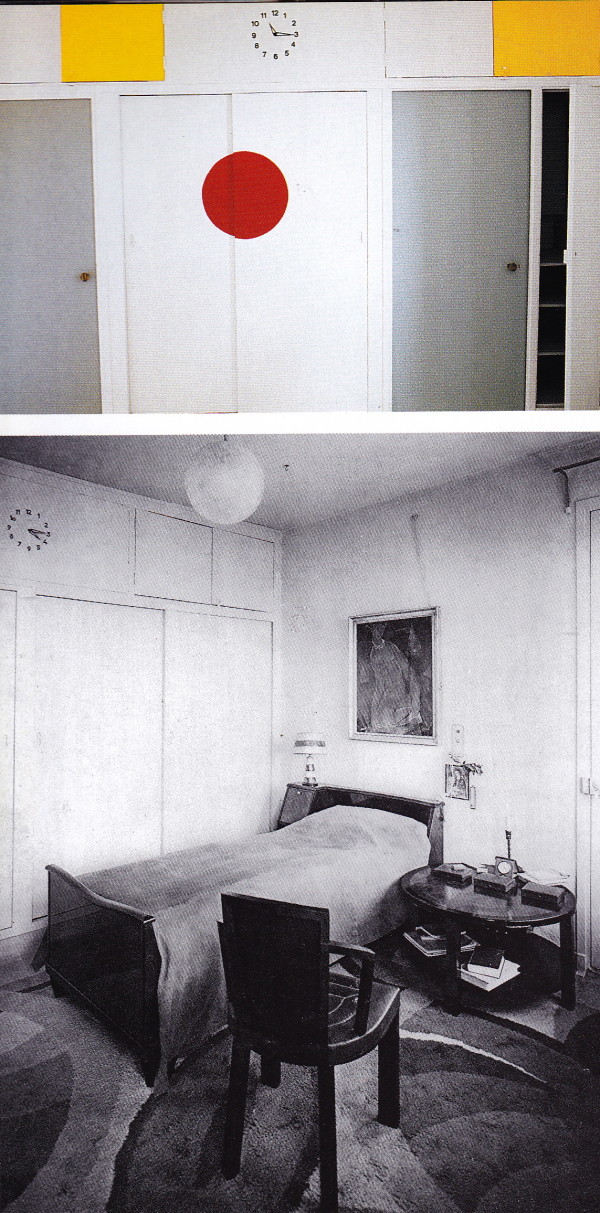

Catroux installed an oeil-de-boeuf window in a guest room that retains Provençal simplicity.

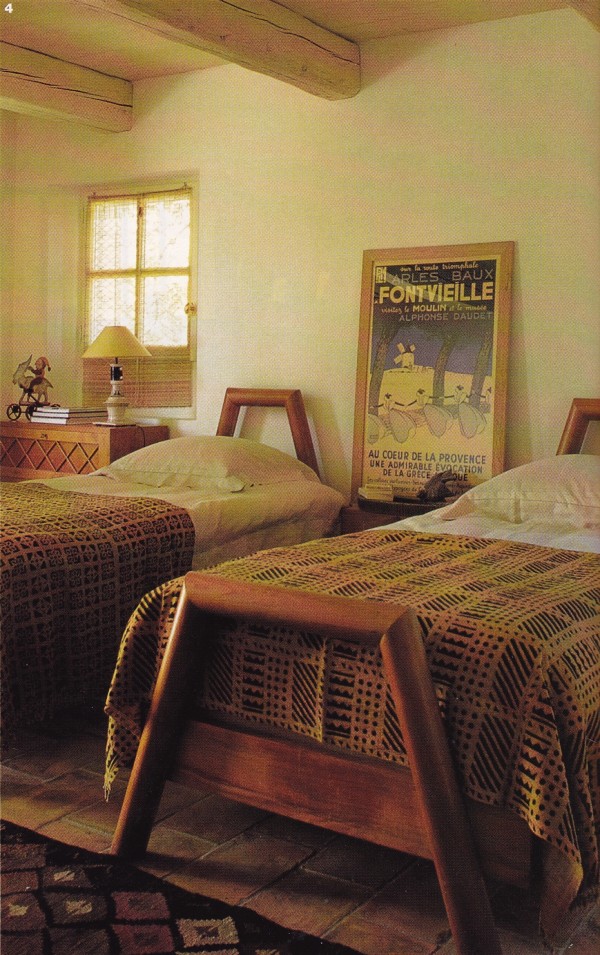

Soothing simplicity and a light touch continue into this guest room.

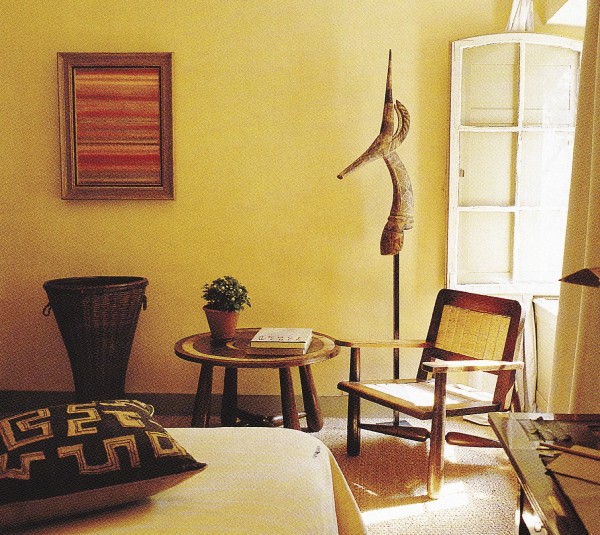

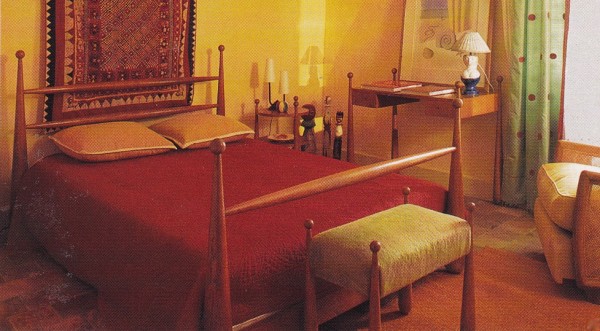

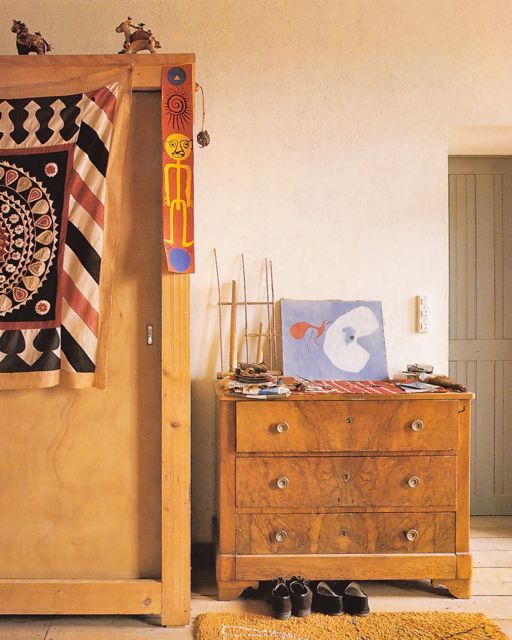

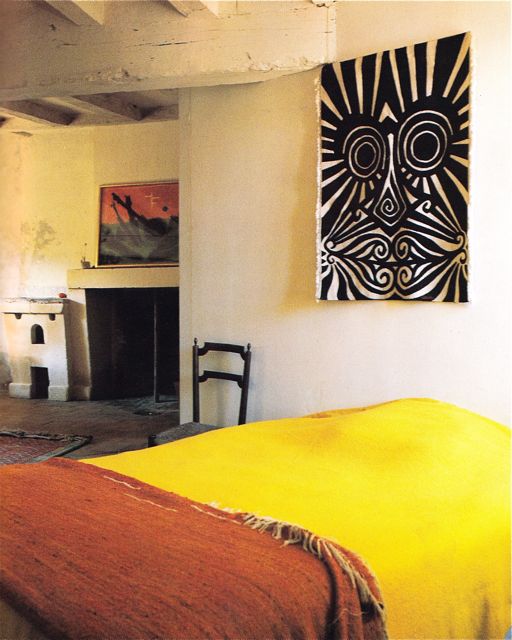

African art and decor adds a bold, masculine rusticity to another guest room washed in the golden hue of local hay.

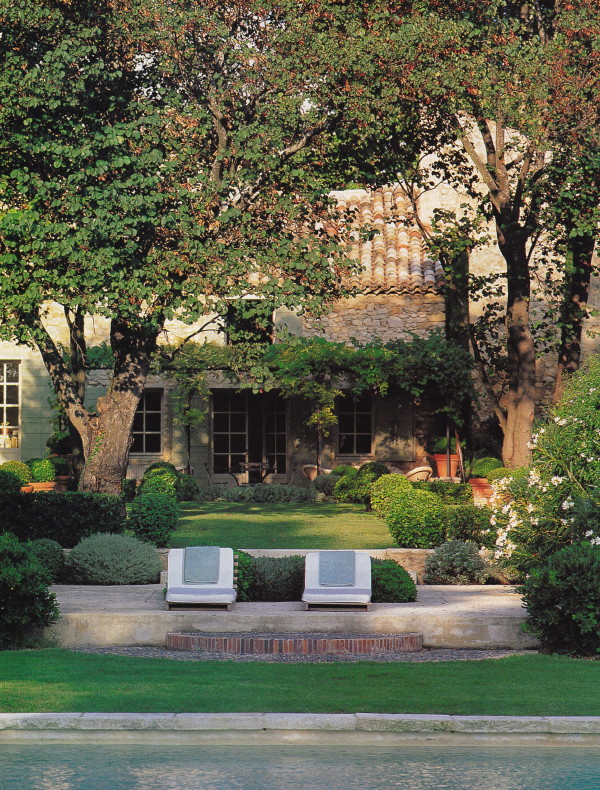

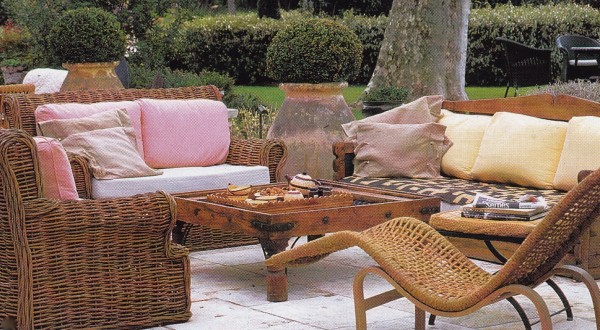

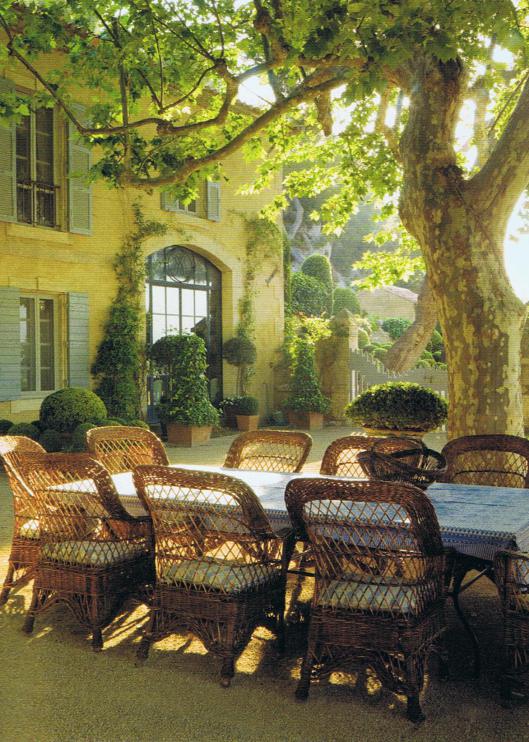

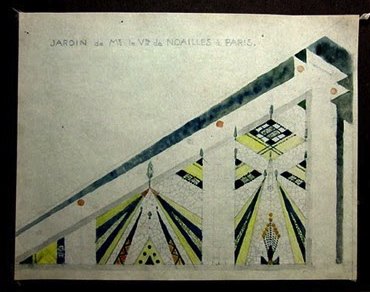

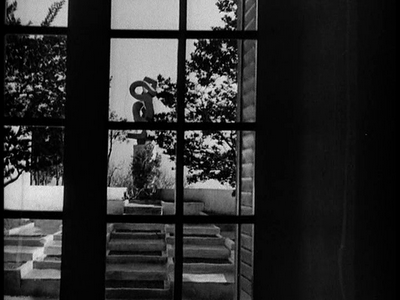

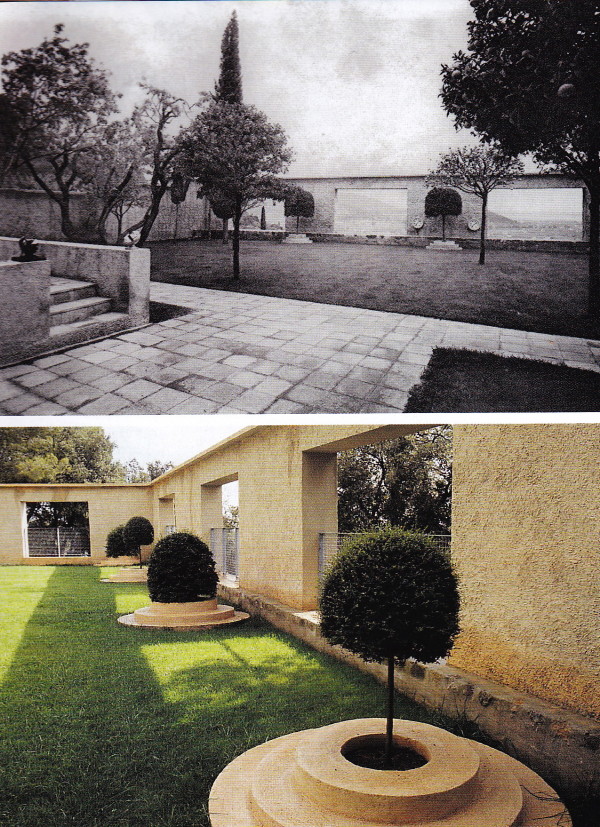

Catroux enlisted landscape designer Dominique Lafourcade to assist with the garden. Topiary laurel trees border the path to the swimming pool. An inviting golden glow beckons within the mas.

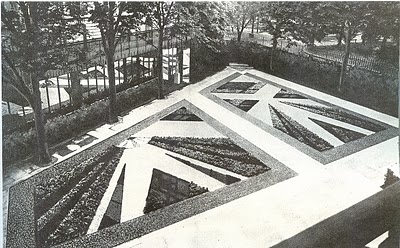

The same view in reverse; the trellis was designed to enclose the terrace with views toward the fountain and pool beyond. The same diamond-patterned flooring extends outdoors, furthering the indoor-outdoor quality of living.

Perfect simplicity, order and balance extends to the layout of the gardens and pool.

Recently Les Ramades was photographed by François Halard for the Wall Street Journal on-line edition. I have provided a link to the feature, with text by David Netto, at the close of this post.

Little has changed aesthetically since the early 1990’s, save for the addition of mid-century modern table lamps and an over-scale hourglass.

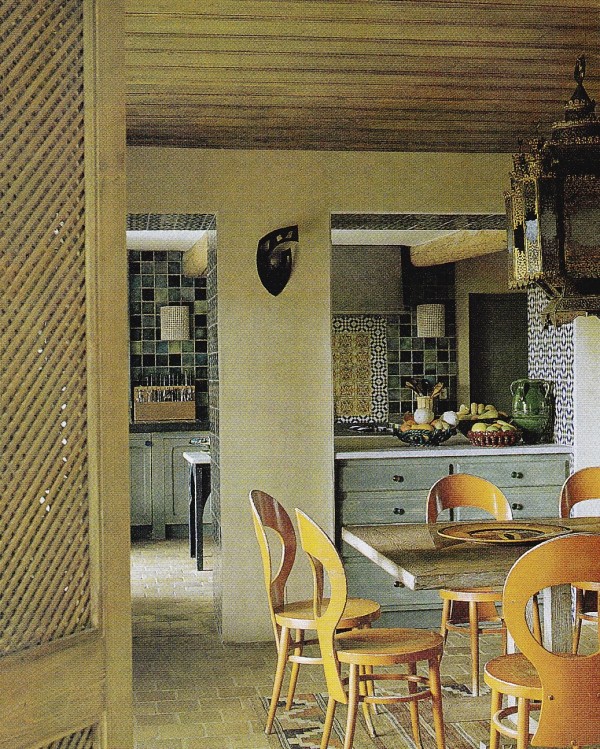

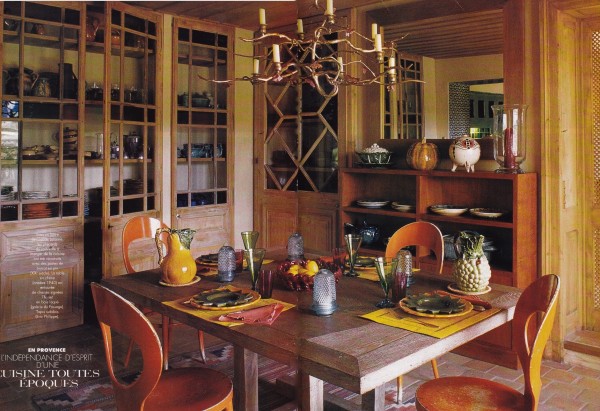

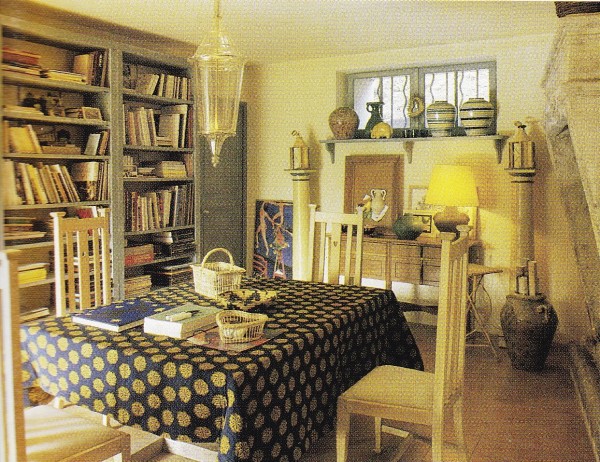

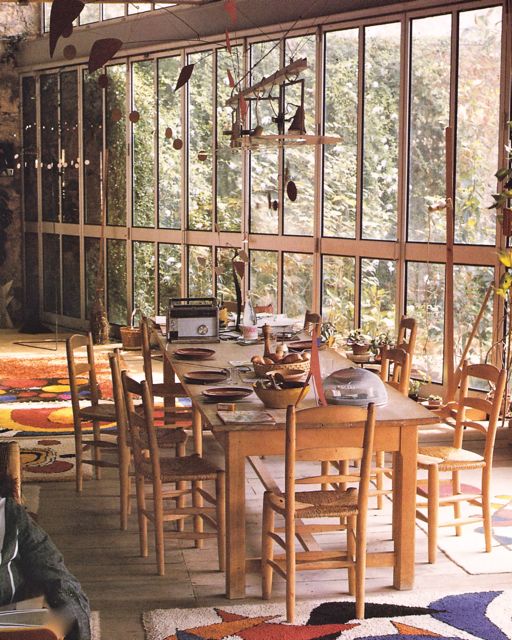

A new arrangement in the center salon provides garden-theme dining, bringing the outdoors indoors, injecting effortless informal chic.

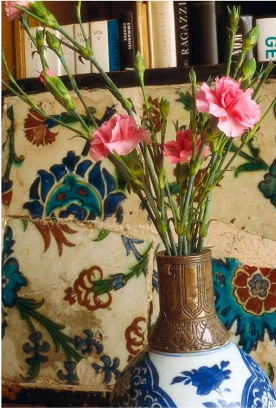

A garden theme also pervades the dining lounge where botanical prints, green pottery and foliage add a dose of verdant lushness.

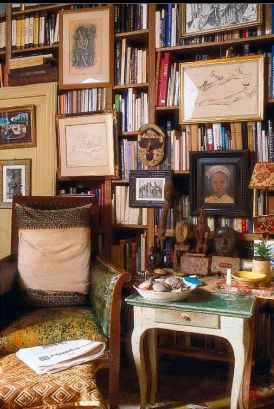

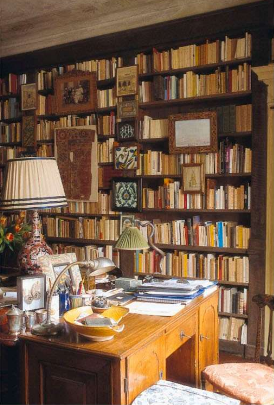

Little has changed in the library … a chesterfield in the same style as the tufted leather one is now upholstered, and Matisse ink drawings flank the bookcase.

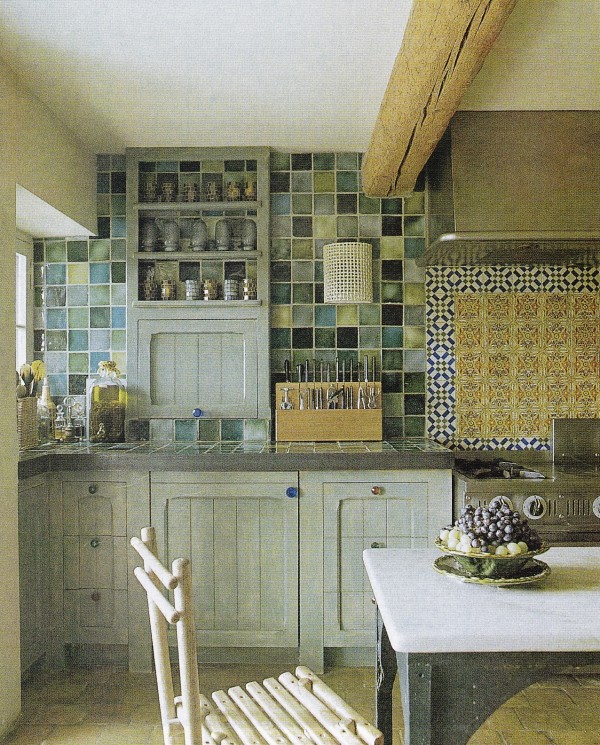

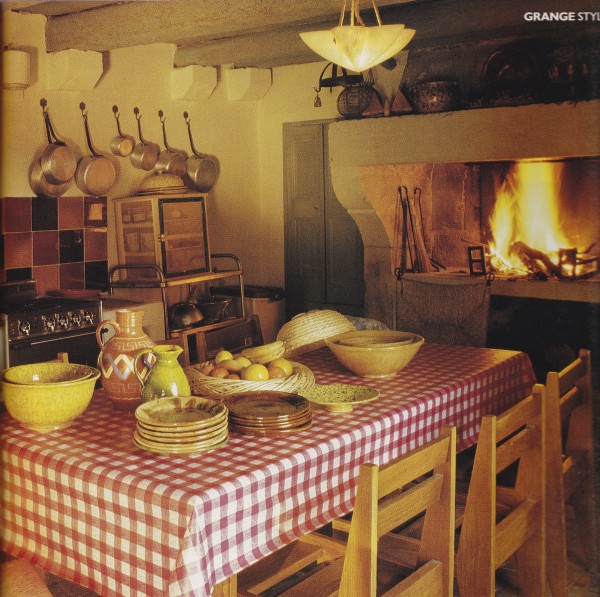

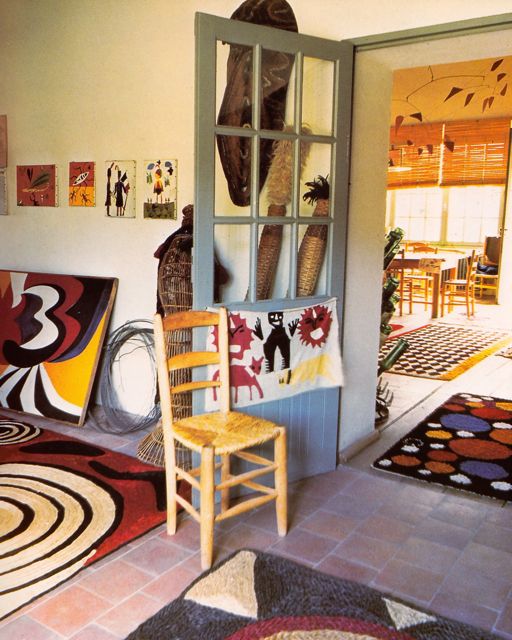

A Calder rug enlivens the kitchen, complimented by a bull’s mask that once hung in the library.

The most marked change can be found in the master bedroom, where a decidedly more French style has taken over with the addition of Louis-XV-style bergères and a pair of iconic plaster consoles by Emilio Terry, and the obvious verdant color scheme.

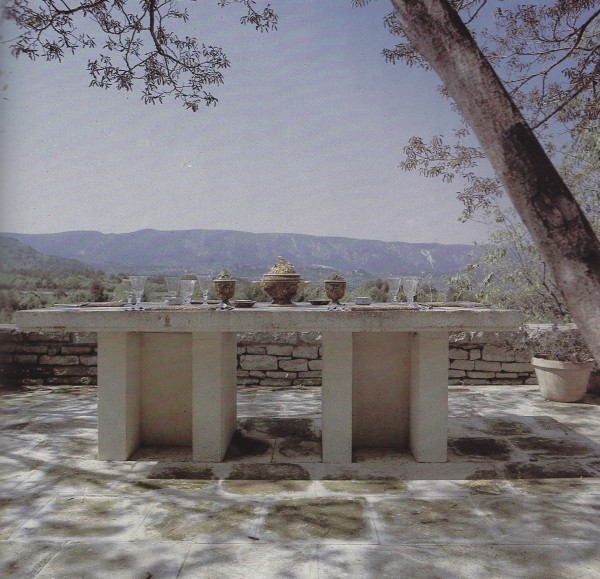

An outdoor dining terrace is hung with lanterns from Vietnam.

An axial view of the swimming pool beyond an allée of trees in the formal gardens bordered by globe topiary and boxwood.

Fields of lavender are bordered by cypress.

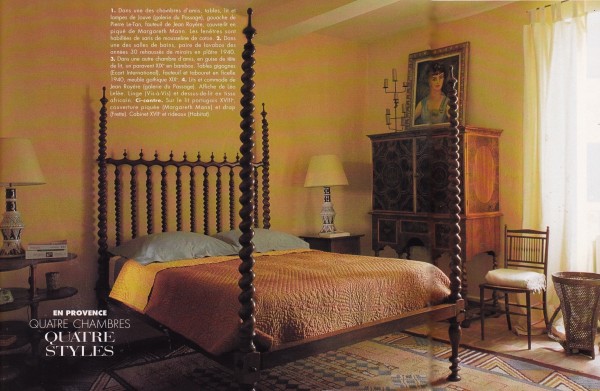

Les Ramades exemplifies rustic chic and quiet elegance at its best, with a look and feel perfectly suited to the Provençal countryside. Although not mentioned previously, my next post will feature the one-time Provençal mas of Dick Dumas, whom I almost overlooked until I rediscovered him flipping through vintage magazines.

For more information on the homes and career of François Catroux read The Catroux of Paris and Provence written by David Netto for the Wall Street Journal.