After completing five posts on wondrous curiosity cabinets I am ready for a breath of fresh air; ready to leave the dark, cramped quarters of magpie collectors and their intellectual pursuits for wide open spaces and understated luxury. I’m ready for a vacation on the French Riveria at the Villa Noailles.

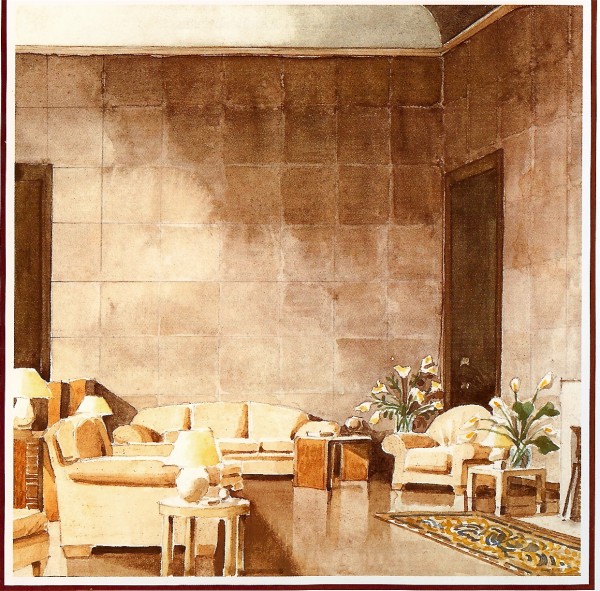

The de Noailles name should ring familiar. In my inaugural post I introduced one of my favorite rooms, the iconic parchment sheathed salon of Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noailes at their Paris hôtel particulier, Hotel de Bischoffsheim, designed by Jean-Michel Frank in 1929. Still earlier, in 1923, the Princess de Poix presented her son, the Vicomte Charles de Noailles, with a parcel of land above Edith Wharton’s restored Castel St Claire in Hyères as a wedding gift. The villa they would commission would forever transform the quaint landscape peppered with classic estates and romantic villas along the French Riviera.

The Vicomte and his new wife, the madcap Marie-Laure – granddaughter of the Comtesse Laure de Chevigné, who inspired Proust’s character, the Duchesse de Guermantes, and distant relative of the Marquis de Sade – was famous for breaking with tradition and adopting unconventional ideals. She placed herself smack at the center of one of history’s most creative decades, the twenties, cultivating a circle of like-minded creatives – writers, poets and artists – who would come to define Surrealism and the modern art movement.

For their villa in Hyères the de Noailles contracted Robert Mallet-Stevens, who was earning a reputation for his luxurious, comfortable take on modernism. Several years prior to meeting Jean-Michel Frank, who would introduce her to le style Frank, Anne-Laure became stifled by the opulence of her Paris mansion with its art-lined walls and formidable antiques. She delighted in the avant-garde and the obscure and set out to create something new and boundary-breaking for their villa on the Riviera. On the site of the ruins of a 9th-century Cistercian monastery the couple broke with local traditions.

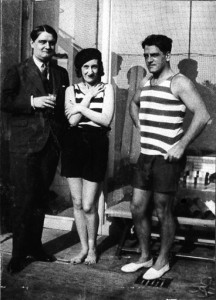

In a photo by Man Ray an eccentric collection of revelers join the de Noailles for a party at the villa.

After interviewing Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier the couple commissioned the architects’ arch-enemy, Robert Mallet-Stevens. Mallet-Stevens’ style was worldly, less austere than late Bauhaus or early Le Corbusier. He bridged French Art Deco and high style Modernism with an eye toward luxury gleaned from the Wiener Werkstatte in Vienna. His uncle had commissioned Josef Hoffman to build Palais Stoclet, an icon of 20th-century modern architecture with an emphasis on the hand-crafted, luxurious and highly stylized Classical deriviations. Hoffman’s elegantly rendered cubist forms greatly influenced Charles’ aesthetic development which carried over to his vision for Villa Noailles.

Imagine the approach to Villa Noailles: It’s 1923. Modernism, particularly in these parts, was an anomaly. Traditionalists would have certainly found it an affront to the romantic ideals of this particular region. This, after all, was not the big city. But the curious and unconventional found it exhilarating. This was a style entirely new, a reductive and less decorative style than French Art Deco. It represented a time of invention and reinvention. The Villa Noailles introduced the chic of the new.

The blocked and exaggerated forms introduced by the forefathers of Cubism, Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, in 1909, continued on into the 1920’s, influencing architects, decorators and product designers.

While the Bauhaus argued that art should meet the needs of society and that there should be no distinction between form and function, and Mies van der Rohe espoused the cool intellectualism of building “machines for living”, Robert Mallet-Stevens adopted a more pared-down and comfortable approach incorporating luxurious materials. His goal was to “make modern architecture the universal architecture, known and loved.”

By another decade we would become familiar with these cubist forms piled one upon another like Mayan temples. But it was Mallet-Stevens’s early work that had a potent influence on the development of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne. And it wouldn’t be until a revival of Art Deco in the 1980’s that enthusiasts would come to discover and appreciate the extent Mallet-Stevens early architecture had on the development of the Art Deco style in France where it was introduced to the world at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Moderne in 1925, the Paris design show that defined le style Art Deco, the popular version of Modernism. In fact, two years into building Villa Noailles Mallet-Stevens participated in the exposition, featuring his Pavilion of Tourism.

A view of the entry hall features stylistic wall sconces, luxurious benches, and a stained glass window in the door beyond on the landing.

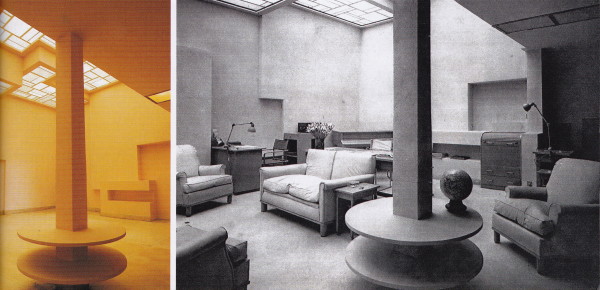

The Salon Rose, now and then, featuring a geometric glass ceiling designed by Louis Barrilet. The style is neither backward looking nor too coolly modern, a sensual departure from the rigid dogma put forth by his contemporaries. With the assistance of architect and decorator Djo-Bourgeois, Mallet-Stevens conceived a comfortable style with soft upholstery and curvaceous forms based on classic models.

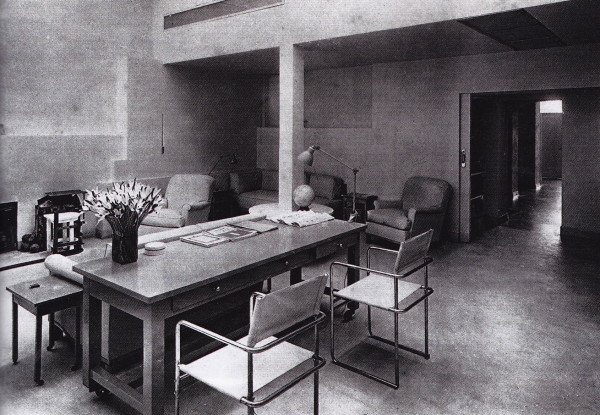

Another view of the Salon Rose, used by Charles de Noailles as his office. The tubular steel chairs were designed by Mallet-Stevens for the villa.

A view of the dining room exhibits lustrous wood veneers, elegant proportions, and decorative embellishment.

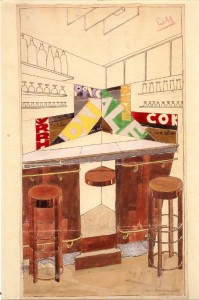

Illustration of a proposal for the design of a bar by Djo-Bourgeois, architect and decorator, who conceived some of the key rooms of the villa.

Another view of an area of the dining room conceived by Djo-Bourgeois.

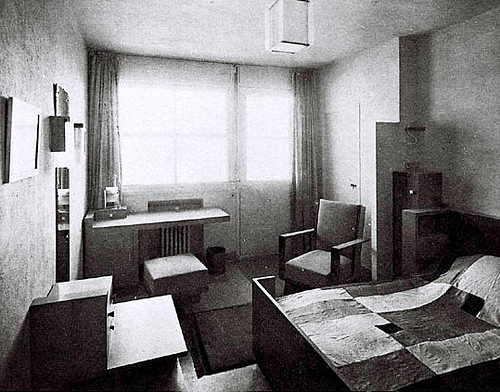

This bedroom features cubist furnishings, lighting and bed cover.

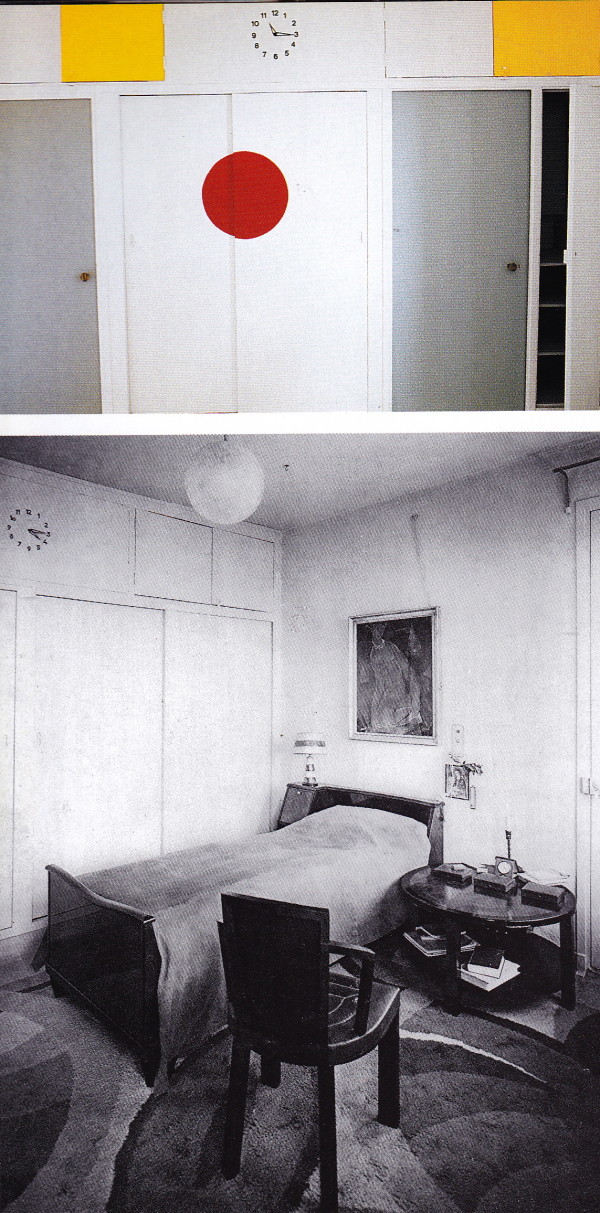

In another bedroom curves take precedence, from the globe ceiling fixture to the rounded forms of the furnishings, to the swirling pattern of the carpet. Every room has an identical clock designed by Francis Jourdain driven by a single central mechanism.

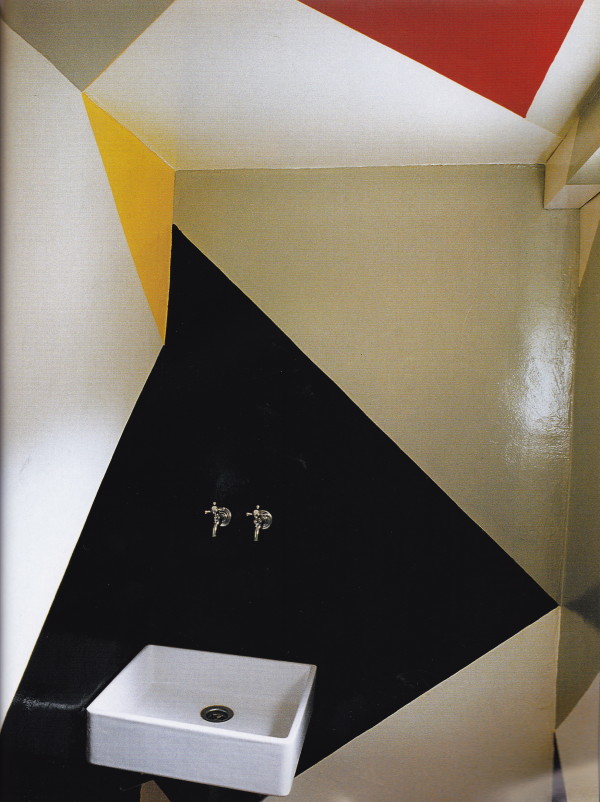

On the walls of the room where flowers were arranged is a cubist pattern of primary colors created for the de Noailles by Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg, the founder and leader of de Stijl.

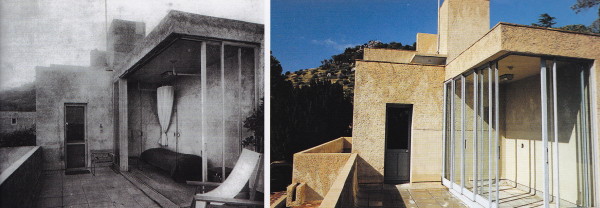

Preferring nature to the indoors, Charles commissioned designer Pierre Chareau to devise an open-air bedroom, featured above, then and now.

While the interiors were within the realm of Marie-Laure’s vision, Charles focused his attention on the gardens and the design of a gymnasium. A man of nature, he often visited the gardens of his neighbor, Edith Wharton, down the hill. He took upon himself the design of the villa’s gardens with the assistance of three garden designers. Charles was also an admitted fitness enthusiast and was known to require his wife’s artist friends to join him in exercise. This theme would spill over into the Surrealistic movies filmed at Villa Noailles by Jacques Manuel and Man Ray, one of which I have included at the close of this post.

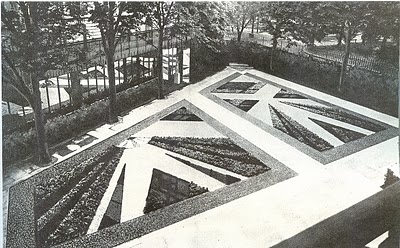

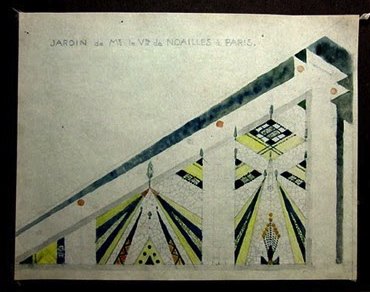

The de Noailles’ commissioned two high Art Deco gardens for their villa. Modern parterres by brothers Andre and Paul Vera featured colorful bands of gravel and low plant beds designed in a stylized sunburst pattern.

A rendering by the Vera brothers illustrates the proposed design while Man Ray’s photo is the only documentation of its installation.

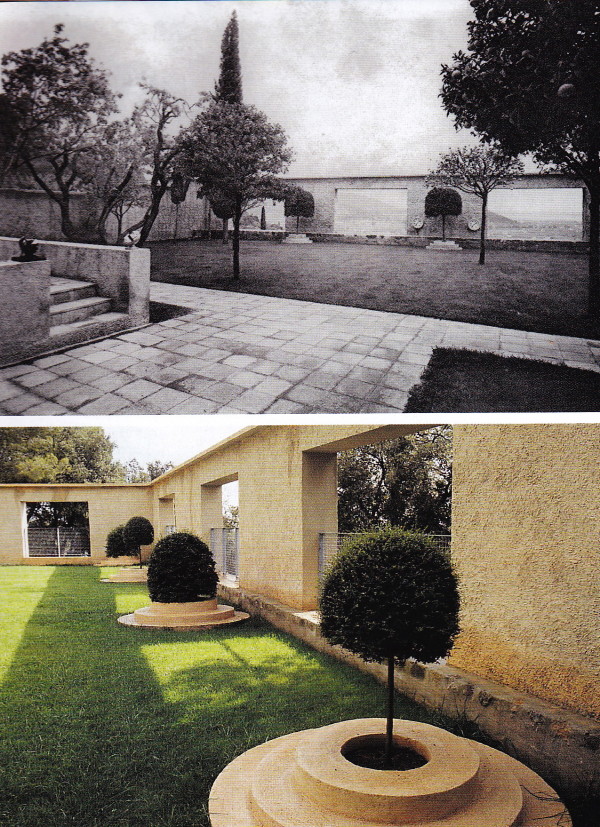

The other high Art Deco garden was the Cubist garden designed by Gabriel Guevrekian, photographed above as it appears today.

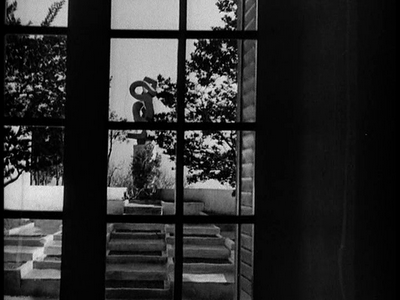

The stepped ziggurat garden designed by Gabriel Guevrekian can be glimpsed through windows from inside the villa. A Jacques Lipchitz sculpture at the garden’s edge rotated, which is featured in Man Ray’s film.

Jean Cocteau, André Gide, Marie-Laure de Noailles and Georges Auric leafing through Max Ernst’s The Hundred Headless Woman at the Villa Noailles, Hyères. Photography by Marc Allégret; January, 1930.

A formal lawn, the site of games of boules, is framed by topiaries and the walls of the swimming pool, then and now.

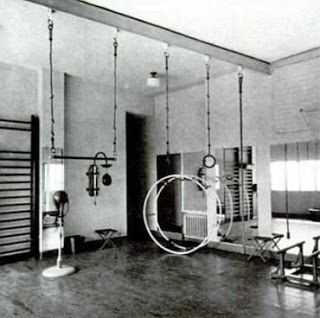

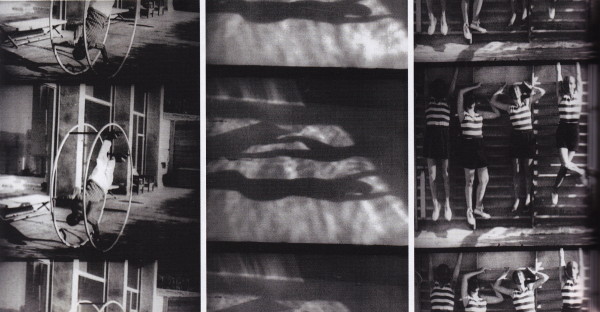

In a vintage photo of the gymnasium is pictured an exercise contraption that one climbs into and rolls, also featured in the film by Man Ray.

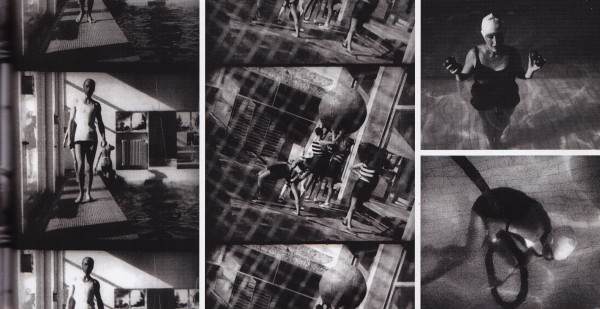

The indoor swimming pool was the focus of many fêtes and featured in two short films, Biceps et Bijoux (1928) and Les Mystères du Château de Dé (1929). The ziggarut design of the perforated ceiling mimics the Art Deco garden designed by the Vera brothers. On the wall is another clock by Francis Jourdain. The metal-and-canvas deck chairs were designed by Mallet-Stevens.

In 1928 the de Naoilles’ commissioned surrealist filmmaker Jacques Manuel to create Biceps et Bijoux, an informal film intended for home-viewing, offering an amusing glimpse into daily summer life at their villa in the late 20’s, featuring the couple and their group of friends exercising together in matching striped bathing costumes.

In 1929 Man Ray recorded life at Villa Noailles in a Futurist film titled Les Mystères du Château de Dé. In the film still at right is Marie-Laure in the swimming pool.

For a truly surreal experience, step back into the privileged world of the de Noailes’ at their villa in Man Ray’s oddly futuristic film. It’s a bumpy ride, literally – the camera shakes, rattles and rolls as the driver ascends the road up to the villa on the hill. Enjoy the view. Bathing suit optional.

http://www.ubu.com/film/ray_chateau.html

Cast:

Alice de Montgomery, Eveline Orlowska, Bernard Deshoulières, Charles de Noailles, Marie-Laure de Noailles, Marcel Raval, Lily Pastré, Etienne de Beaumont, Henri d’Ursel, Jacques-André Boiffard, Man Ray

Photography attributed to Jacques Dirand courtesy of The World of Interiors, July, 2001.

Pingback: Monsieur Moderne – Part Quatre | Cristopher Worthland Interiors