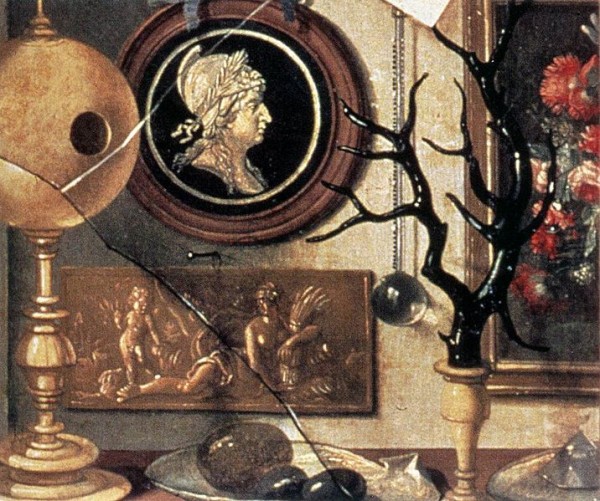

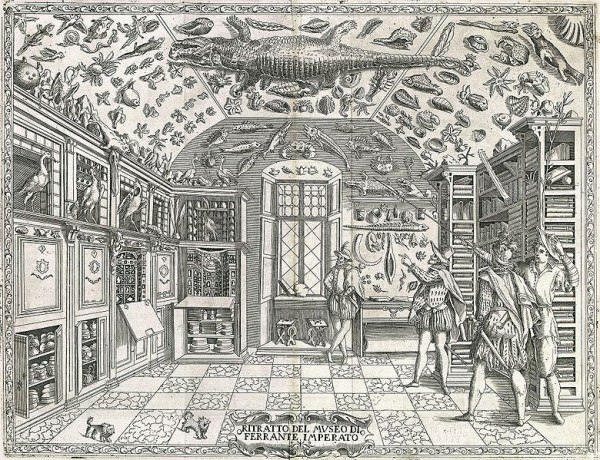

Engraving from Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’Historia Naturale (Naples 1599), the earliest illustration of a natural history cabinet.

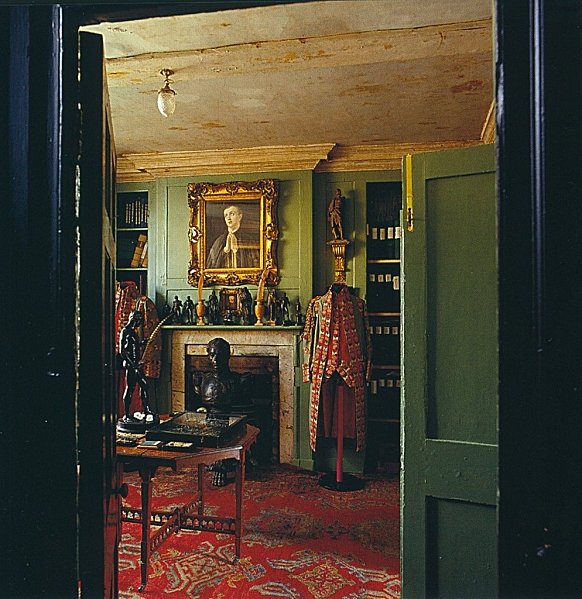

A Soanian niche door surround was installed by the mansion’s one-time owner, brewer Harry Charrington, 1790’s. Photo by James Mortimer.

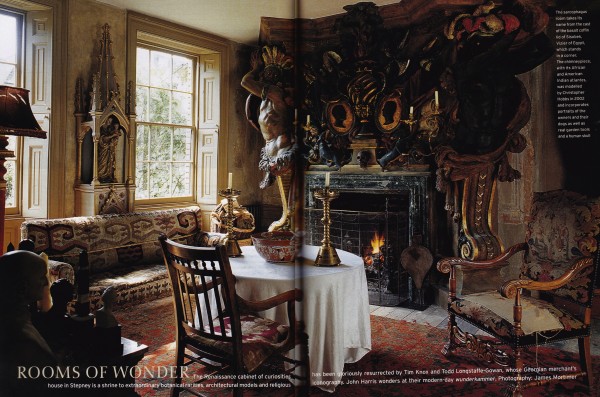

Tim Knox (head curator of the National Trust) and Todd Longstaffe-Gowan (a landscape architect and historian) are keeping the tradition of the Renaissance cabinet of curiosities, with its taste for eccentric oddities, alive in their London merchant’s house of 1741, Malplaquet House. Their rooms transport us back to the Naples of 1599 illustrated above by Ferrante Imperato, with their vast collections of religious artifacts, art work, busts, architectural models, taxidermal animals and other curiosities acquired from the markets and auction houses of England.

The sarcophagus room takes its name from the cast of the basalt coffin lid of Sisobek, Vizier of Egypt, which stands in a corner. Photo by James Mortimer for The World of Interiors.

The Baroque fireplace surround designed by Christopher Hobbs incorporates African and Indian atlantes in reverence of the inhabitants origins, and portraits of the owners and their dogs, as well as real garden tools and a human skull. Photo by Barry Lewis

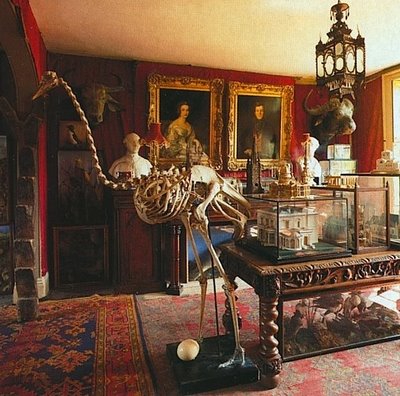

One of the first rooms a visitor approaches is the Bird Room, above and below,created by the affluent brewer Harry Charrington in the 1790’s out of two paneled closets from 1741. Trophy heads line the walls alongside portraiture, and a skeletal ostrich watches over its egg while architectural models cover every surface.

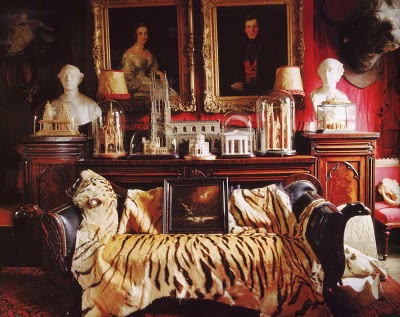

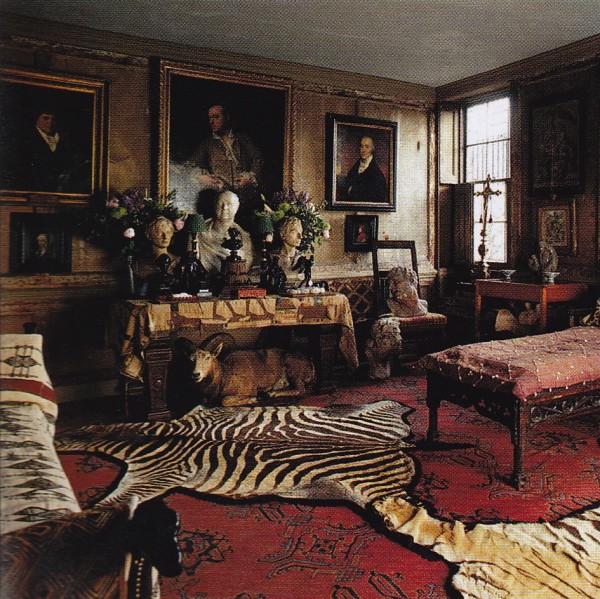

The drawing room, above and below, is lined with portraits and tables bursting with busts. Below, a painting of a man with a harelip by Adriaen Carpentiere overlooks a bust by Samuel Joseph of Field Marshal Lord Beresford, ‘butcher of Albufiera’. Resting underneath the table is a stuffed Indian goat from Kelvedon Hall.

Adjacent to the drawing room is the museum, above – a cabinet of curiosities including death masks, shells, and naturalia. A portrait by Henri Pierre Danloux of a Scottish widow in her white weeds hangs above the fireplace. The plaster “death masks” are from left: Tim, Todd, Canova, an unidentified hippy, Mirabeau and, on the étagère, Napoleon.

Part of a collection of paintings of nuns flank a carved chest crowned by a water buffalo in a vestibule. Photo by Barry Lewis

Next along the tour come two studies. John Harris describes the first, the anteroom of which is pictured below, as “a private catalog room, blessed by a saint in ecstasy flanked by the state livery of the 3rd Earl of Ashburnham”, made in 1829 and encrusted with armorials.

The other study, above, is a 1790’s Regency scheme of gray paneling with borders of delicate reeded paper which contains the desk on which Alfred Waterhouse designed the Natural History Museum.

The basement lobby looking towards the sculleries. The original, crumbling paint has been retained where possible. Photo by James Mortimer.

One-hundred-and-eighty cubic meters of earth and rubble were removed to reveal the buried Georgian basement kitchen. Now with floors covered in time-worn pavers and walls lime-washed in sunny yellow, could you not picture yourself here discussing your next acquisition over a steaming cup of tea from India? I can almost smell the scones baking. Photo by James Mortimer.

The top floor can only be accessed by facing the judgement of game trophies. Photos by James Mortimer.

One must pass the scrutiny of the Virgin and Child on the stair landing, which originates from the Anglican convent of Woking founded by Matilda Gibbs of Tyntesfield. Photo by Derek Henderson.

Crucifixes and embossed memorial pictures line the lime-washed walls of a bathroom. Photo by James Mortimer.

Rooms such as these are not for everyone, and many would find it difficult to live among such eccentric and often macabre collections of oddities. For me they are not about decorating or interior design, but of atmosphere – atmosphere rich in history; of travel to far-flung, exotic locales, of collecting with a constant curious eye. They inspire story-telling and dreaming – or perhaps nightmares, depending on your disposition.

While one would be hard pressed to find other similar cabinets of wonder today – the kind that embrace the eccentric Renaissance ideal of collecting oddities – the tradition of collecting by antiquarians continues on. In my next post we will visit the collections-filled London flat of antique dealer Peter Hinwood.

Photos taken by James Mortimer for the October, 2003, issue of The World of Interiors.