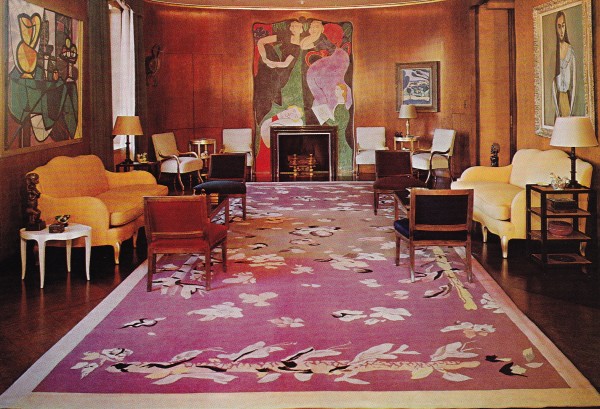

Nelson Rockefeller was not your ordinary, staid politician. By the late nineteen thirties he had amassed an enviable art collection of Modern masters – Braque, Picasso, Matisse, Gris, de Chirico, Leger, among many other examples, in addition to a primitive art collection. To house his collection of art and artifacts he called on no other than Jean-Michel Frank, the French interior designer who invented modern interiors.

Rockefeller was a deeply curious, modern man. John Loring wrote for Architectural Digest, “Of all the members of the family, Neslon Rockefeller, through a winning combination of imagination, impulsiveness, an eye for quality, a taste for adventure, and as he said, ‘fate’, amassed the most extraordinary collections..” When Rockefeller commissioned Frank to create interiors for his newly expanded Fifth Avenue deluxe apartment he was treasurer of the Museum of Modern Art. Frank’s vision for Rockefeller’s new apartment in 1937 would become not only the first example of his work in the U.S. but one of the most artistically important. Rockefeller was well-informed on le Style Frank, having visited the famous minimally luxe lair of the Victomte and Vicomtesse de Noailles in Paris, which Frank designed for them in 1926.

Fast forward to the early nineteen-nineties: Margaretta “Happy” Rockefeller, Nelson’s second wife, married in the sixties, is a widow. The apartment that Wallace Harrison and Raymond Hood (architect of Rockefeller Center and the Metropolitan Opera House) constructed and Jean-Michel Frank designed was still in tact, just as it was in 1937. It consisted of two expansive floors at 850 Fifth Avenue – much too large for Happy’s modern day lifestyle. Over lunch one day with Albert Hadley she asked if he would take a look at it. Happy explained, “I want a more do-able, cozier apartment for myself and my two sons. My only insecurity was to find myself with all those marvelous things and to want so much to know that Nelson would be proud of how I used them. The apartment had to keep the feeling of something we had done together.” No longer entertaining heads of state, Happy desired a more comfortable and private domain.

The late, great Albert Hadley was a devout admirer of Jean-Michel Frank’s contribution to design: “It was a turning point in the decorative arts, a beginning of simplicity in form. All that incredible furniture, with its echoes of Louis XV and Louis XVI and Charles X, has great meaning, for many reasons. It would have been criminal to have gotten rid of any of it.”

The transposition of the original layout began with scaling down the size of the apartment, which would come to comprise primarily of a wing that had been added twenty years prior by Wallace Harrison. Albert Hadley’s sensitivity to Frank’s masterpiece and Happy’s desire for a more comfortable environment were realized, retaining most of the original custom designed Frank furniture.

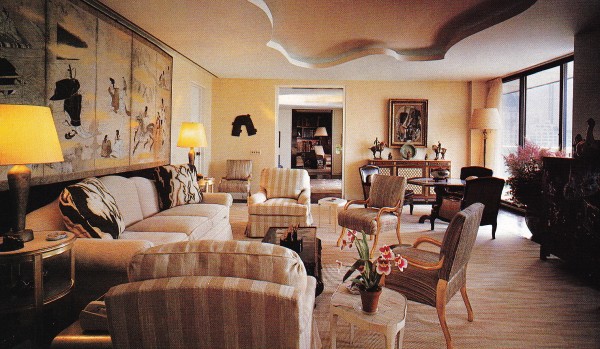

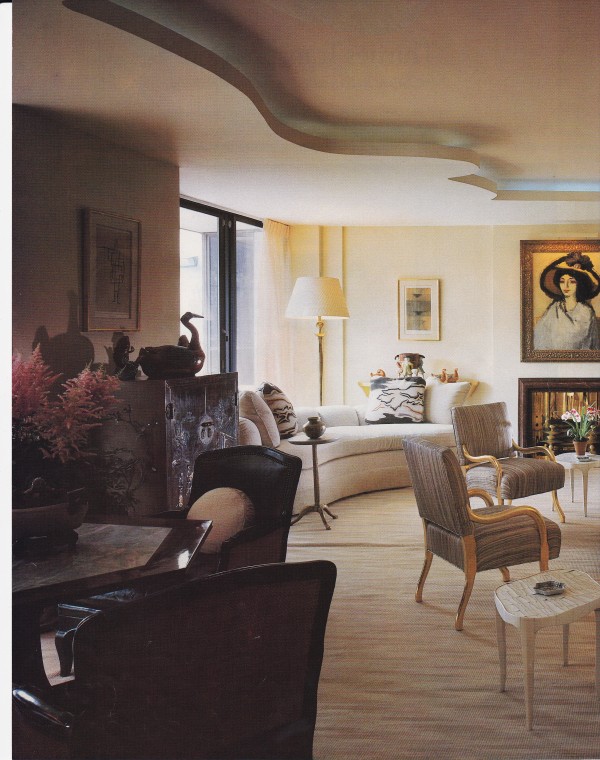

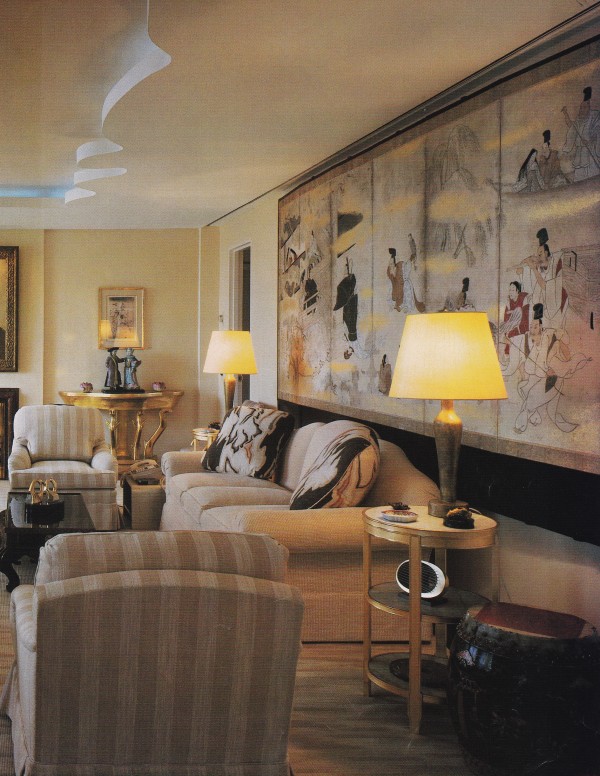

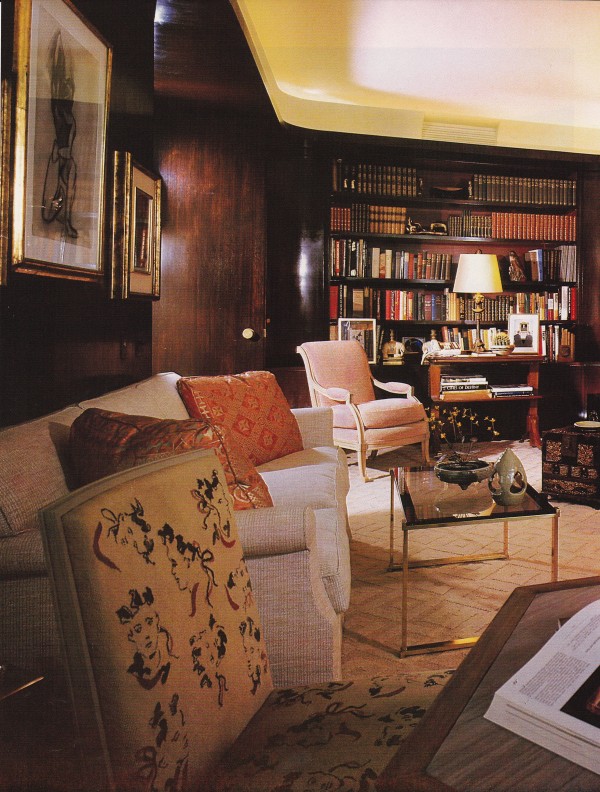

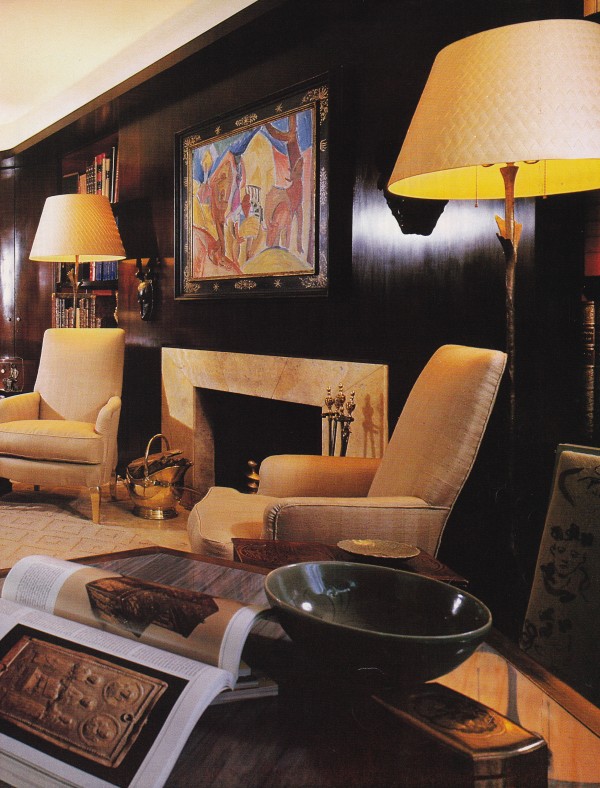

What had originally been the master bedroom was reconfigured into the present living room by Albert Hadley. A ceiling cut-out design by Fernand Léger is original to the room. Recognizable from the original Frank wood-paneled living room are a pair of gilt wood bergeres and ivory veneered tables by Frank in the foreground, and a pair of gold consoles and andirons by Giacometti on the far wall. The marble fireplace mantel also came from the original living room. The reproduction van Dongen painting over the fireplace is flanked by two small works by Paul Klee.

Happy Rockefeller’s bedroom before it was reconfigured as a living room by Albert Hadley. Other than the for the original cut-out design in the ceiling by Léger the room displays no signs of Frank’s work.

The scheme for the new living room was based on the colors of the Edo period Japanese screen that Mrs. Rockefeller admired, taken from their country house. Hadley assured Mrs. Rockefeller that he would endeavor to use as much of her diverse artworks as possible. The gold foil in the Japanese screen, the gilt finished lamps by Giacometti and gilt bergers and side tables by Frank contribute to what Hadley remarked is “the goldest room you’ve ever seen”.

The new living room exhibits a fondness by Mrs. Rockefeller for Asian decorative arts, as seen again her with the Japanese screen, polychrome porcelain figurines, lacquered cocktail table, glazed fish bowl and robes chest. The neutral upholstered furniture added by Hadley is perhaps too plump and over-scaled for today’s tastes but, nevertheless, contributes to a sense of ease and comfort in keeping with the scale of the space. A furniture layout comprising three distinct groupings lends the space a convivial spirit.

The first dining room mirrored the original paneled living room designed by Wallace Harrison and Jean-Michel Frank, a photo of which I have never seen. After Rockefeller expanded the apartment in the 1960’s after purchasing an entire floor of the building next door because it obscured their view he transformed the former dining room into a gallery, fashioning a new dining room from the original guest bedrooms.

The Rockefeller’s dining room in the 1960’s featured an abstract wall mural created by Fritz Glarner in 1964. Philip Johnson designed the black-lacquered and leather-upholstered chairs. Elaborate candelabra and candle sticks infuse the room with a sense of grandeur.

In the dining room’s third incarnation Hadley replaced the vibrant mural with glamorous, shimmering tea-paper. The original dining room’s dining chairs – which Fritz Glarner replaced with ones designed by Philip Johnson in the 1960’s – were reintroduced, still wearing their original petit-point upholstery by Christian Bérard. At left is an etching by Picasso. The painting is by Massimo Campigli. The alabaster jar on the pedestal is ancient Egyptian.

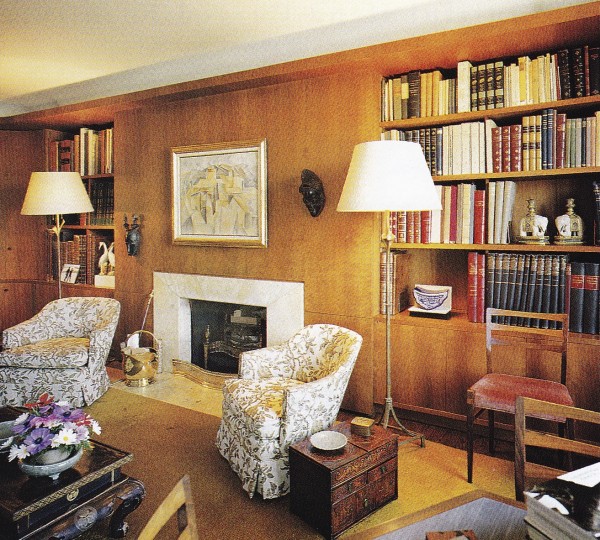

The library, above, retains its original cherrywood paneling in a darker finish. The painting duplicates a Picasso bequeathed to MOMA. A pair of Frank-designed arm chairs flank the fireplace in front of Giacometti floor lamps, which remain in situ, as seen in the photo of the same room, below, taken some time in the sixties. A burnished Giacometti table lamp sits atop a books table at the far end of the room. African masks retain pride of place as they had years prior. Hadley successfully evoked le style Frank compared to the more happenstance decor illustrated in the photo below, with its pair of chintz covered armchairs that appear out of place.

The Rockefeller’s library as it appeared in the 1960’s. Early Asian and African art mixes with modern works, such as Giacometti’s lamps and Picasso’s Maisons Sur La Colline, Horta de Ebro, 1909.

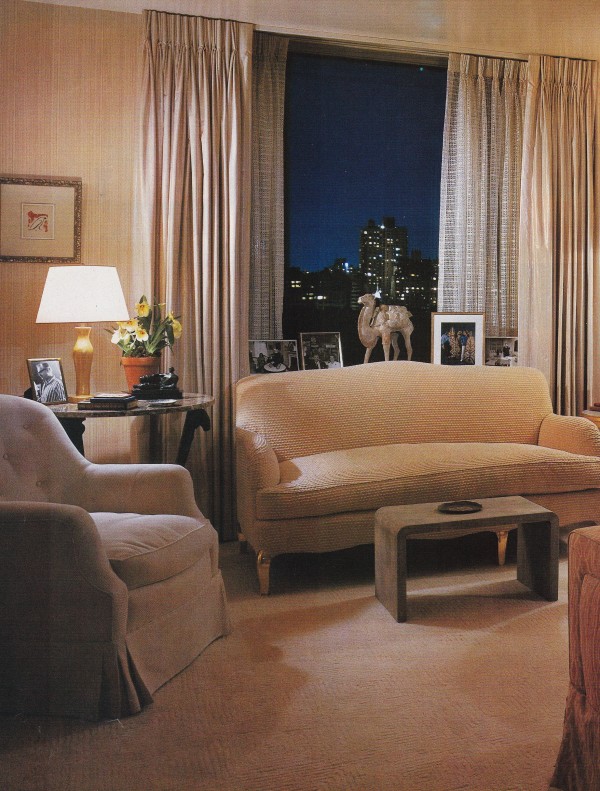

A comfortable mix of furniture upholstered in honeyed tones lends a luxurious warmth to Happy Rockefeller’s bedroom suite, with a sofa design by Frank and club chair by Hadley. The gilt lamp is by Giacometti; the green shagreen table by Frank (taken from the original living room); the small bronze is by Henry Moore.

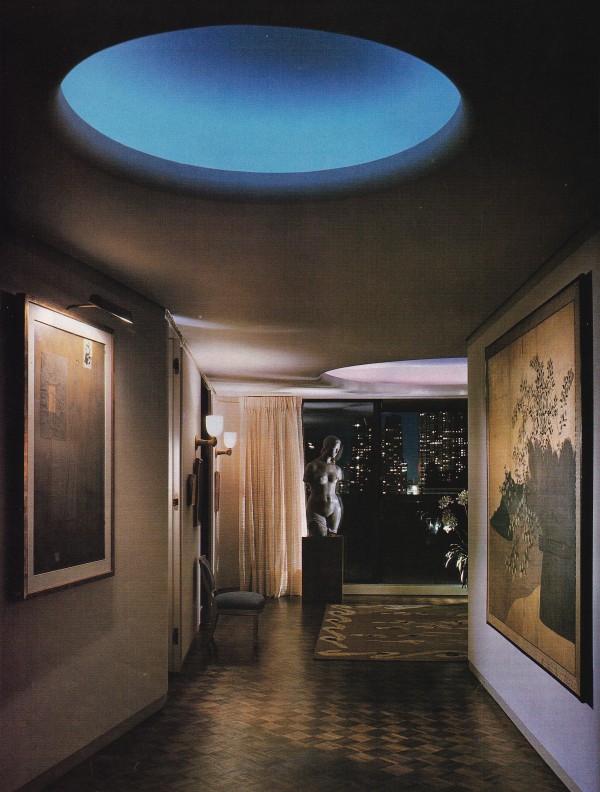

The dramatically lighted gallery was originally the dining room. In the nineteen-sixties Nelson Rockefeller expanded the apartment by buying an entire floor of the building next door because it obscured their views from the dining room. Surrealist sconces by Giacometti and a chair by Frank. At the end of the hall is the Aubusson area rug by Christian Bérard used in the original living room nearest the mural by Léger.

Albert Hadley, considered by many “the dean of design”, developed a sympathetic design resolution by bringing together the diverse Rockefeller collections in a comfortably luxurious, seemless setting. The sense of cutting edge glamour is somewhat lost on the reincarnation of Frank’s interiors by Hadley, (which perhaps is exactly what Happy Rockefeller wished for), as they convey a more conventional approach to assimilating past with present, especially in the living room. Yet, either way, any admirer of Jean-Michel Frank would be smitten at the off chance that they could live among such style-defining treasures as those appearing in these images. Sadly, every room, and every incarnation, is but a memory. They no longer exist as they once did. It’s a tragedy that the original Frank rooms were not removed and donated to an institution, such as the Met, for posterity, as were the Wrightsman rooms. As Nelson Rockefeller himself commented on these rooms, “It’s got a warmth that is really quite exciting. It combines a lot of qualities of the past, but done in a contemporary way. There’s richness and quality with the simplicity of the modern, and these things mix together very well. It’s ideal.”

Content for this post taken from Jean-Michel Frank Remembered by Van Day Truex for Architectural Digest, and Thirties Transposition by John Loring for Architectural Digest.